Archive

Why a 4.5% Nominal Rate is Roughly Equilibrium…Hmmm, Sounds Familiar…

I was planning to write today about why a 4.5%-5.0% nominal Treasury rate is not only not the end of the world, but actually sort of normal. Naturally, the reason I am even thinking about the topic is because of all of the apparent alarm because the current long bond recent peeked above 5% and the 10-year note at 4.50% continues to flirt with those levels. Because we haven’t seen the 10-year rate above 5% for a sustained period in about 18 years, it is natural that some of the young folks who were raised in an era of free money would think that this is the end of the world.

I’ve previously written about the return of some of the phenomena that we used to take for granted, such as the presence of optionality in the bond contract. After most of two decades of unhealthy interest rates produced unhealthy leverage habits among other unwelcome developments (including the leveraging of the government balance sheet because it was so cheap to borrow for one’s programs with no cost), I suppose it shouldn’t be surprising that there is so much wailing and gnashing of teeth, rending of garments, etc. But for those people who expect the Fed to lower rates significantly, because “after all 2% is the normal level of interest rates,” I am here to say that you probably don’t want the crack-up that would be necessary to make that plausible. The current level of interest rates is inconvenient for many organizations with a borrowing problem, but it is really quite normal.

Anyway, I’d intended to write a longer version of that, and as I started to write something bugged me and I looked back and noticed that I’d already written essentially the same thing a few years ago. At the time (June 2022) I was explaining “Why Roughly 2.25% is an Equilibrium Real Rate,” and of course if you add reasonable inflation expectations of 2.5%-3% you get to 4.75%-5.25% as an equilibrium nominal rate (and a bit higher than that for the 30-year, which also incorporates a modest additional risk premium). If you go and read that article directly, you can also get my screed on how models trained on the last 25 years of data leading up to the inflation spike only survived if they forecast a very strong reversion to the mean, and so *eureka* all of those models missed the entire inflation spike. But here is a reprinted snippet (reprinted by permission from myself) outlining the argument for why the current level of long-term real interest rates is about right.

Kashkari made a different error, in an essay posted on the Minneapolis Fed website on May 6th.[1] He claimed that the neutral long-term real interest rate is around 0.25%, which conveniently is where long-term real rates are now.

However, we can demonstrate that logic, reinforced by history, indicates that long-term real rates ought to be in the neighborhood of the economy’s long-term real growth rate potential.

I will use the classic economist’s expedient of a desert-island economy. Consider such an island, which has two coconut-milk producers and for mathematical convenience no inflation, so that real and nominal quantities are the same. These producers are able to expand production and profits by about 2% per year by deploying new machinery to extract the milk from the coconuts. Now, let’s suppose that one of the producers offers to sell his company to the other, and to finance the purchase by lending money at 5%. The proposal will fall on deaf ears, since paying 5% to expand production and profits by 2% makes no sense. At that interest rate, either producer would rather be a banker. Conversely, suppose one producer offers to sell his company to the other and to finance the purchase at a 0% rate of interest – the buyer can pay off the loan over time with no interest charged. Now the buyer will jump at the chance, because he can pay off the loan with the increased production and keep more money in the bargain. The leverage granted him by this loan is very attractive. In this circumstance, the only way the deal is struck is if the lender is not good at math. Clearly, the lender could increase his wealth by 2% per year by producing coconut milk, but is choosing instead to maintain his current level of wealth. Perhaps he likes playing golf more than cracking coconuts.

In this economy, a lender cannot charge more than the natural growth in production since a borrower will not intentionally reduce his real wealth by borrowing to buy an asset that returns less than the loan costs. And a lender will not intentionally reduce his real wealth by lending at a rate lower than he could expand his wealth by producing. Thus, the natural real rate of interest will tend to be in equilibrium at the natural real rate of economic growth. Lower real interest rates will induce leveraging of productive activities; higher real interest rates will result in deleveraging.

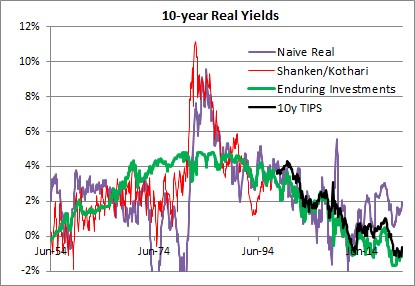

This isn’t only true of the coconut economy, although I would strongly caution that this isn’t exactly a trading model and only a natural tendency with a long history. The chart below shows (1) a naïve real 10-year yield created by taking the 10-year nominal Treasury yield and subtracting trailing 1-year inflation, in purple; (2) a real yield series derived from a research paper by Shanken & Kothari, in red; (3) the Enduring Investments real yield series, in green, and (4) 10y TIPS, in black.

The long-term averages for these four series are as follows:

- Naïve real: 2.34%

- Shanken/Kothari: 3.13%

- Enduring Investments: 2.34%

- 10y TIPS: 1.39%

- Shanken/Kothari thru 2007; 10y TIPS from 2007-present: 2.50%

It isn’t just a coincidence that calculating a long-term average of long-term real interest rates, no matter how you do it, ends up being about 2.3%-2.5%. That is also close to the long-term real growth rate of the economy. Using Commerce Department data, the compounded annual US growth rate from 1954-2021 was 2.95%.

It is generally conceded that the economy’s sustainable growth rate has fallen over the last 50 years, although some people place great stock (no pun intended) on the productivity enhancements which power the fantasies of tech sector investors. I believe that something like 2.25%-2.50% is the long-term growth rate that the US economy can sustain, although global demographic trends may be dampening that further. Which in turn implies that something like 2.00%-2.25% is where long-term real interest rates should be, in equilibrium.[2] Kashkari says “We do know that neutral rates have been falling in advanced economies around the world due to factors outside the influence of monetary policy, such as demographics, technology developments and trade.” Except that we don’t know anything of the sort, since there is a strong argument against each of these totems. Abbreviating, those counterarguments are (a) aging demographics is a supply shock which should decrease output and raise prices with the singular counterargument of Japan also happening to be the country with the lowest growth rate in money in the last three decades; (b) productivity has been improving since the Middle Ages, and there is no evidence that it is improving noticeably faster today – and if it did, that would raise the expected real growth rate and the demand for money; and (c) while trade certainly was a following wind for the last quarter century, every indication is that it is going to be the opposite sign for the next decade. It is time to retire these shibboleths. Real interest rates have been kept artificially too low for far too long, inducing excessive financial leverage. They will eventually return to equilibrium…but it will be a long and painful process.

At the time I wrote the passage above, 10-year TIPS yielded about 0.25%; today they yield 2.125%. It turned out that returning to equilibrium wasn’t at all a long process. But it certainly was painful!

Returning to the original point: just because 10-year rates are now approximately at equilibrium is not at all a prediction that they will remain at equilibrium. Indeed, if I made that prediction I would be making a very similar mistake to the one I criticized above. Mean reversion in rates is not a particularly powerful force, when set against an active central bank and a profligate legislature. But if it matters at all, it is very important to correctly identify the mean to which rates should revert.

And it’s not 2%.

[1] https://www.minneapolisfed.org/article/2022/policy-has-tightened-a-lot-is-it-enough

[2] The reason that real interest rates will be slightly lower than real growth rates is that real interest rates are typically computed using the Consumer Price Index, which is generally slightly higher than the GDP Deflator.

Illustrating the Cost of Leverage Effect on Returns

A couple of weeks ago, I presented a blog post called “The Effect of Crazy Time on Portfolio Allocations,” in which I pointed out that the effect of increasing volatility generally is to decrease the optimal portfolio allocations towards safer allocations. It was one of those posts where you initially say ‘well, duh’ but hopefully liked the fact that I ‘proved’ the intuition with the illustrations. While market volatility since then has been almost unbelievably low, it is hard for me to imagine that is sustained. It feels a little like a ‘deer in the headlights’ reaction from investors, as the Trump Train comes on so rapidly that all they can do is pull the shades.

I suspect that at some point, unless the Donald suddenly becomes a milquetoast business-as-usual kind of President, we will see those allocations shift.

But a few days ago I had another realization that called to mind the same old CFA-Level-I charts. I was explaining to someone who wanted me to leverage our really cool inflation-tracking strategy[1] that leveraging a mid-single-digits return makes a lot of sense when the cost of leverage is zero, but not so much sense when the cost of leverage was mid-single-digits. I’ve talked about this before – in October 2023 I published “Higher Rates’ Impact on Levered Strategies.”[2] I showed a table, but there’s a really simple way to illustrate the same thing.

I don’t really need the portfolio efficient frontier here. Maybe the optimizer spits out some share of the optimal portfolio that represents an investment in some hedge fund strategy you really like. Maybe it doesn’t. More likely, you don’t even use an optimizer. But if you really like that strategy, but want higher returns, you ask the manager ‘hey, can you lever that’? The manager says sure. But the manager can’t give you twice the returns for twice the risk – the leverage math doesn’t work that way. If the cost of leverage is 3% – which you can tell it is in this chart because that’s where the line hits the axis, at a risk-free rate of 3% – then your return for twice the risk is (2 x 4% – 1 x 3%) = 5%. So you pick up only 1% return for doubling the risk. And you can see that on the chart, because that’s the point the red line goes through: 5% return, 15% risk. For 3x risk, you get (3 x 4% – 2 x 3%) = 6%. And so on. The slope of the line is such that 7.5% additional risk gets you 1% additional return, no matter how many times you lever it.

So why do people ask for leverage? Well, because since 2008 the overnight rate was mostly at 0%.

If you can borrow at zero then levering simply multiplies risk and return simultaneously. At 2x leverage, your return is (2 x 4% – 1 x 0%) = 8%. You can see where this goes since 0 times anything drops out of the formula.

But this doesn’t work at higher costs of leverage. If the cost of leverage is equal to the expected return, then you just get more risk every turn of leverage you deploy. And if the cost of leverage is above the expected return, you make things worse every time you add leverage.

So it doesn’t make any sense to lever low-return strategies unless the cost of leverage is really low. And by the way, it doesn’t make much sense to lever high-return strategies unless they happen to be low risk. Because this math doesn’t just work with expected returns but also (and more importantly) with actual returns. Suppose you have a strategy that has a 6% expected return and a 15% risk. Say, an equity index. Now, you lever it 2x with the cost of leverage at 5% (by the way, if you use a levered ETF you’re not escaping the cost of leverage…but that’s for another day). Your expected return is now 7%, with 30% risk (check your understanding by doing the math).

Now, however, you get a 2-standard deviation outcome to the downside. Supposedly that happens only one year out of 40, but we know that there are fat tails in equity markets. But whatever the real probability, your unlevered return is now 6% – 2 x 15% = -24%. But now you’re riding the lightning and your return on the 2x leverage is (2 x -24% – 5%) = -53%. (Alternatively, you get to the same number if you just look at the new 7%ret/30%risk portfolio return as 7% – 2 x 30%).

Hedge fund managers understand this math…or should; if they don’t then get out…and it should change the numbers they report in forward-looking statements when interest rates are higher, for levered strategies. I will not comment on normal industry practice…

[1] To be clear, none of the red dots in this article represent the risk/return tradeoff for that strategy. I’m not trying to cagily present our fund’s performance because that would get me in trouble.

[2] This was a golden era for the blog. Right about the same time I also published one of my best posts in years, pointing out how the CME Bond Contract has shortened in duration and also has negative convexity again. “How Higher Rates Cause Big Changes in the Bond Contract.” How I loved that piece.

The Effect of Crazy Time on Portfolio Allocations

I am continually fascinated by how many second-order ‘understandings’ are missed, even by those people who have a really good first-order understanding of finance. For example, every financial advisor understands that bonds are less volatile than stocks. Most financial advisors understand that stocks and bonds in a portfolio together also benefit because they’re not correlated. Some financial advisors, and most CTAs, understand that diversifying a portfolio works because when you add uncorrelated assets together, the risk of the whole is less than the sum of the risks because of the offset from the correlation effects. Those are all coarse understandings that any financial professional should ‘get.’ However, it is fairly unusual for advisors or even CTAs to understand that the correlation of stocks and bonds undergoes a state shift when inflation get above about 2.5% for a few years, and become correlated, and that means more risk for the same combination of stocks and bonds. Here’s that chart I love to show, updated through the end of the year.

While that’s an example of a ‘second-order understanding’ that isn’t widely known, it isn’t what I want to write about today. Actually, for a change what I want to discuss is something that has nothing directly to do with inflation, and that is the effect of volatility on asset allocation.

This is an important discussion right now, because whether or not you have gotten the message yet that President Trump is going to be much more Machiavellian in his approach to the global world order than prior Presidents have been – and whether you think that’s a good thing or a bad thing – you surely must have noticed that the volatility of the markets under this regime is likely to be somewhat higher than under Sleepy Joe and also higher than it was during Trump’s first term. And that leads to the second-order understanding about what that implies for markets. Hang with me here; if you’re not a finance person this gets a little hairy.

The next chart shows Modern Portfolio Theory on one chart.

The blue line is the Markowitz efficient frontier: every point on the line represents a portfolio of assets that is the least-risky for that level of expected return. So, the highest vertical point is a portfolio of 100% in the asset with the highest expected return…you can’t get more return without leverage.[1] In this case, let’s assume that is equities. As you go down the curve, you allocate more to other less-risky assets and give up some portfolio return. Because assets are not 100% correlated, you can always get a portfolio that has at least as good (and usually better) returns for a unit of risk than any single asset – that’s the benefit of diversification. As you get to very low expected returns, you get to the part of the curve you’d have to be irrational to be on because you get higher risk and lower returns, and so we usually ignore that part of the curve that bends back.

The red line is popularly called the “Capital Asset Line.” Assuming there is some zero-risk instrument (that’s not already in the assets we’ve considered, so there’s some hand-waving here) and you can both borrow and invest at that rate, you can think of a portfolio that is the ‘best’ portfolio on the blue curve, either combined with the zero risk instrument (sliding down the red line to the left) or levered at the zero risk instrument (moving up the red line to the right). The ‘best’ portfolio here is defined as the place where the red curve is tangent to the blue curve.

A lot of times you’ll just see those two lines, but it doesn’t answer the question of which portfolio an actual investor prefers. It turns out that investors do not have linear risk preferences…that is, if I make my portfolio 10% more risky, perhaps I require 1% more return but if I make it another 10% risky, I’m going to need more than 1% additional return. I’m not only risk averse, but I get more risk averse the larger the potential risks. [Lots of experimental data on this. If I offer you a bet where you pay me $1 and on the basis of a coin flip I will either pay you $2 or $0, you are much more likely to take that bet than if I offer you a bet where you are risking $10,000 for the chance at $20,000…or zero]. So the purple dotted line is a hypothetical ‘investor indifference curve’. I just made up that term because I can’t remember what the theoreticians call it. The curve represents all of the combinations of risk and return that make the investor equally happy. So, the best portfolio for this investor is where the purple line – the highest purple line we can find, indicating the MOST happiness – touches the red line.

With me? Now consider the next chart. All I have done here is to increase the risk of every asset and shift the whole portfolio efficient frontier to the right.

What happens? The Capital Asset Line (red) now flattens out. And that means that the prior purple line no longer has a point of tangency. We have to go to a lower purple line, and since the purple line is concave upward the red line becomes tangent to the purple line at a point further to the left (the slope of the red line is flatter, and the flatter parts of the purple line are to the left). I’ve put the new ‘optimal portfolio’ as a dot in purple.

The implication is this: if overall risk in markets is perceived to have permanently increased, then rational investors will move from portfolios with more risky assets to portfolios with fewer risky assets.

You probably could have guessed that without all of the curves. If I am comfortable with a certain amount of risk, and the overall risk of things goes up, then it stands to reason that I’d work to reduce my overall risk. The second-order understanding here is, then, that if President Trump is perceived by investors to increase the overall volatility in markets and individual country and company outcomes, we should expect investors to lighten up on equities.

And that brings me to the final chart. This is the Baker, Bloom and Davis news-based Economic Policy Uncertainty Index, which counts the number of articles in US-based news sources that contain a set of predefined terms that indicate uncertainty about economic policy. The dotted lines below show weekly data; the heavy red line shows the 12-week moving average to get rid of the noise.

Notice the three prior spikes on the chart are during and immediately following the end of the internet/stock market bubble in the early 2000s, the end of the housing bubble and the Global Financial Crisis in 2008-09, and the COVID crisis. All three of those episodes were associated with significantly lower markets, although you could argue that harsh bear markets might trigger some policy uncertainty (that certainly happened after 2008). The jump on the right is the Trump jump, and it is already higher than any other period on this chart other than COVID.[2] Volatility we have. Uncertainty we have. And even if you like the President’s policies, the volatility means that we should not be surprised to see investors pull some chips off the table.

[1] If you take this best-returning asset and leverage it, you basically get a straight line going up and to the right forever; the slope of the line depends on the cost of leverage.

[2] Incidentally, the index goes back to about 1985 and although I didn’t show it there are two more bumps that are similar to the leftmost two on this chart: around the 1993 recession, and around the time of the stock market crash in 1987. They are all lower than the Trump jump.

Inflation Market Valuations and Tactics in the New Year

There is so much to talk about, since it has been such a long time since I posted, that it is a little hard to know where to begin. So let’s begin 2025 with a few quick notes about inflation markets and markets generally. I wouldn’t call this an outlook, per se…I am trying to resist making that year-end/year-beginning offering to the jinx gods…but an update with some observations. As an aside, later today I’m planning to post a new Inflation Guy Podcast (this is a Podbean link but it’s available anywhere you get your podcasts) with some comments on the trajectory of inflation (as opposed to markets), and how that may be affected by things such as the massive California wildfires.

I will begin with a content warning: this note is much denser than most of my columns. If you’re a retail investor and/or only interested in developments in inflation rather than inflation instruments, then you might skip this one. I’ll talk more about expectations for inflation, of course, in other posts. But that’s not today’s post.

Let’s start by looking at 10-year real yields. The blue line in the chart below is 10-year TIPS yields; the black line (because it’s topical) is 10-year UK Gilt linker (real) yields. TIPS yields are up to 2.25%. Normally, when they get to around 2% I think of them as roughly fair in an absolute sense, because long-term risk-free real yields ought to in principle look something like long-term real economic growth. Instructive in the chart below is that as far as nominal UK yields have risen, inflation-linked yields are still well below US real yields.[1]

That’s partly a clientele effect, since there are many forced holders of UK linkers. But still, while US real yields ran up from -1% to +2.25% once inflation started (that is, TIPS declined in a mark-to-market sense when inflation went up – very, very important to understand if you think of TIPS as an inflation hedge. They are, but only at maturity), Gilt real yields went from -3% to +1.19%. The selloff was 100bps worse. Yikes.

The next chart shows my quantitative measure of relative cheapness (negative indicates richness, because I’m a bond guy). I said before that TIPS are now roughly fair in an absolute sense; relative to nominal bonds, they’re also roughly fair to slightly cheap. That’s the blue line. You can see that TIPS for most of the past decade were pretty cheap relative to nominals (even while they were absolutely rich because of negative real yields), but since people started caring a bit about inflation they’ve gone back to being mostly fair. However, Gilt linkers have been massively rich for a long time – again, because of the forced-holders problem. But they are starting to get cheaper. That 100bps greater selloff I mentioned above happens to show up here as 100bps cheapening relative to nominals, and relative to TIPS!

Today’s column is supposed to be mostly about US markets, but I can’t help myself. I ought to also point out that breakeven inflation in the UK is roughly 100bps higher than it is in the US, even though core inflation in the UK is 3.6% and in the US it’s 3.5%. So, possibly, part of the relative richness of UK linkers – since I’m looking at each country’s linkers in relation to its own nominal bonds – is actually cheapness of UK nominals, compared to the actual inflation there. Or maybe it’s the richness of US nominals, compared to the actual inflation here. (This is why relative value trading is so useful and important – we don’t need to have an opinion about which of these two things is true. Are US nominals too rich, maybe because they can be financed cheaply in repo markets at ‘special’ rates? Or are UK nominals too cheap, maybe because the UK budget situation is perceived to be somehow even more precarious than our own? I don’t know.)

Sorry about the digression there to the UK. I just got excited. The inflation markets and inflation in Japan are also really interesting right now, especially as wage growth is surging and the yen is bordering on collapsing…yet 10-year inflation in Japan is quoted around 1.5%. If you can get someone to transact. Maybe I’ll talk about Japan another time.

US markets. First, note the weird shape of the US CPI swaps curve.

I have several issues here, with one of them being the overall optimism that inflation is definitely going back to be close to target, despite any real sign that is going to happen. It borders on religious conviction, frankly. But also, we have a weird implied path where inflation droops, then spikes near the 10-year point, and then declines. To be sure, I’m committing a chart crime here with the y-axis; if you stepped back this would look almost flat. But this is more than enough for a hedgie to be interested, usually. What is really happening is that if we had a core inflation swaps curve (I do, but you don’t) it would show a gentle decline out to 8 years. It’s steep on the CPI swaps curve because the energy curves imply that energy inflation will drag core inflation lower for years.

Of course, they won’t but you can hedge the energy. Out to about 5-8 years, probably. And that’s probably why we have that little dip in the CPI curve – it’s really an energy thing.

So I’ve said that 2.25% real yields on TIPS are fairly attractive. About as attractive as they’ve been for some time, actually. But be aware of a couple of things. One is that the bond market as a whole is under pressure and probably will stay under pressure for a bit as investors worry about financing the government in a world where the trade deficit is probably going to be coming down (implying that domestic savings will have to go up, and the only good way to make that happen is with higher yields). Real yields could go higher, and probably will at some point. But you should recognize that seasonality works in favor of the TIPS buyer right now.

Breakevens have a strong tendency to rise in the early part of the year. In 22 of the last 26 years, 10-year breakevens have risen in the 60 days following January 8th. To be sure, some of that is because TIPS bear flat-to-negative accretions in the early part of the year because CPI in December almost always declines on an NSA basis, so the rise in price/decline in real yields that helps widen breakevens is partly reflecting a change in the source of total return in TIPS during those months to being more price and less yield.[2] The point being that buying nominal bonds in the beginning of the year, up until about May, runs into difficult seasonal patterns but this is not true with TIPS. Indeed, it means that if you’re buying fixed income at all in Q1, it probably should be TIPS.

Finally, I really should say something about equities here. I think it’s always important to realize that TIPS yields are a direct competitor with equities. Nominal yields are not, necessarily, because 7% nominal yields in a world where prices (and earnings) are going up at 9% are much worse than 5% nominal yields in a world where prices (and earnings) are going up at 3%. Equity earnings do tend to rise with inflation (but stocks are a poor inflation hedge because multiples also tend to contract significantly when there is inflation, so you need to hold equities for a long, long time for them to be a good inflation hedge), and since they do it means that inflation-linked yields are a more-fair comparison. Real yields at 2.25% are neither rich nor cheap in the grand scheme of things. But equities are, once you discount expected earnings growth for expected inflation. I calculate the expected long-term S&P real return assuming that the current multiple of long-term average earnings (the Shiller PE) reverts 2/3 of the way to its mean over 10 years. By making it 10 years, and not demanding full reversion, I lessen the impact of apparent overvaluation on expected returns. But high returns do, historically, tend to precede low returns! In any event, you can debate my approach but below you can see my point.

This first chart shows 10-year TIPS yields set against my calculated expected 10-year annualized real returns from the S&P 500. Granted, the S&P 500 is cheaper outside of the Magnificent 7. But you can see that while stocks and TIPS cheapened together in the inflation spike of 2022, equities have ‘forgotten’ that they should be priced for higher real yields…resulting in the chart below, which I call the “Real Equity Risk Premium” of expected equity returns minus TIPS real yields.

Some of you will say “that’s a trend. Let’s get on that and buy stocks.” To me, that sounds like the fellow falling out a window on the 29th floor and declaring as he passes the 6th floor ‘so far, so good.’ The point of the chart is that when you buy stocks now, you should be expecting to lose money, in real terms, over the next decade. Maybe you’ll average 3% and inflation will be 4%, for example. But TIPS will guarantee you will make 2.25% after inflation. As this spread gets more and more tilted against stocks, it gets harder and harder to explain why anyone would choose equity risk over TIPS risk, other than as a diversifier.

[1] This is not wholly unique to the UK. US 10y inflation bonds have higher real yields than linkers in Australia, Italy, Israel, Canada, France, the UK, Germany, and Spain.

[2] This is wonky stuff. If the expected forward price level doesn’t change, then the breakeven needs to go up because we are starting from lower and lower current price levels due to the (short) lag between the reporting of CPI and its realization in the carry of TIPS. If you don’t understand this because you’re not a rates strategist, don’t worry about it and take my word for it.

Re-Blog: Volatility and Position Size

This is one of my favorites, and every few years I re-blog some portion of this article. The original, I wrote in 2010. The basic question is, what is the correct way to respond as an investor to increasing uncertainty? In the original blog and in various re-posting edits, I’ve applied a basic idea called the “Kelly Criterion” to explain why responding to market selloffs by trimming a position, rather than adding to it, is often the right strategy (in the sense of it being mathematically optimal, not in the sense of it always producing the best returns). The idea also applies to the question of what to do when the general level of uncertainty and volatility rises (or falls) in markets. With developing uncertainty in the Middle East and the US spiraling towards what looks to be a summer of crazy politics, it is rational – even optimal – to ‘take some chips off the table.’ Read on for why.

(“Kicking Tails” originally appeared February 12, 2018)

Like many people, I find that poker strategy is a good analogy for risk-taking in investing. Poker strategy isn’t as much about what cards you are dealt as it is about how you play the cards you are dealt. As it is with markets, you can’t control the flop – but you can still correctly play the cards that are out there.[1] Now, in poker we sometimes discover that someone at the table has amassed a large pile of chips by just being lucky and not because they actually understand poker strategy. Those are good people to play against, because luck is fickle. The people who started trading stocks in the last nine years, and have amassed a pile of chips by simply buying every dip, are these people.

All of this is prologue to the observation I have made from time to time about the optimal sizing of investment ‘bets’ under conditions of uncertainty. I wrote a column about this back in 2010 (here I link to the abbreviated re-blog of that column) called “Tales of Tails,” which talks about the Kelly Criterion and the sizing of optimal bets given the current “edge” and “odds” faced by the bettor. I like the column and look back at it myself with some regularity, but here is the two-sentence summary: lower prices imply putting more chips on the table, while higher volatility implies taking chips off of the table. In most cases, the lower edge implied by higher volatility outweighs the better odds from lower prices, which means that it isn’t cowardly to scale back bets on a pullback but correct to do so.

When you hear about trading desks having to cut back bets because the risk control officers are taking into account the higher VAR, they are doing half of this. They’re not really taking into account the better odds associated with lower prices, but they do understand that higher volatility implies that bets should be smaller.

In the current circumstance, the question merely boils down to this. How much have your odds improved with the recent 10% decline in equity prices? Probably, only a little bit. In the chart below, which is a copy of the chart in the article linked to above, you are moving in the direction from brown-to-purple-to-blue, but not very far. But the probability of winning is moving left.

Note that in this picture, a Kelly bet that is less than zero implies taking the other side of the bet, or eschewing a bet if that isn’t possible. If you think the chance that the market will go up (edge) is less than 50-50 you need better payoffs on a rally than on a selloff (odds). If not, then you’ll want to be short. (In the context of recent sports bets: prior to the game, the Patriots were given a better chance of winning so to take the Eagles at a negative edge, you needed solid odds in your favor).

Now if, on the other hand, you think the market selloff has taken us to “good support levels” so that there is little downside risk – and you think you can get out if the market breaks those support levels – and much more upside risk, then you are getting good odds and a positive edge and probably want to bet aggressively. But that is to some extent ignoring the message of higher implied volatility, which says that a much wider range of outcomes is possible (and higher implied volatility moves the delta of an in-the-money option closer to 0.5).

This is why sizing bets well in the first place, and adjusting position sizes quickly with changes in market conditions, is very important. Prior to the selloff, the market’s level suggested quite poor odds such that even the low volatility permitted limited bets – probably a lot more limited than many investors had in place, after many years of seeing bad bets pay off.

[1] I suspect that Bridge might be as good an analogy, or even better, but I don’t know how to play Bridge. Someday I should learn.

When to Own Breakeven Inflation

It is interesting to me that, with as important and liquid as the inflation-linked bond market is, tactical allocation between TIPS and nominal bonds is at best an afterthought for most investors. Perhaps this is because TIPS – if you think in nominal space, like most investors do – can be quirky and complex to analyze on a bond-by-bond basis. Here’s a picture of the TIPS yield curve. The red line is the way that TIPS real yields are calculated, and therefore the curve as perceived in the market. The green line is the true yield curve, adjusting for the way the seasonality of inflation prints affects each particular bond.

That’s understandable, but I don’t think it’s sufficient. Most investors do not invest in individual bonds, especially in TIPS space. They invest via mutual funds or ETFs, although the ‘laddering’ of TIPS to form a crude inflation-linked annuity is a popular approach amongst do-it-yourselfers. So why do so many investors own nominal bonds, instead of inflation-linked bonds, as an immutable strategic allocation? Even those who make occasional tactical shifts into TIPS seem to do so when they are expecting inflation to rise, and so are making a macro call instead of a quantitative call. But there are lots of times when owning TIPS instead of nominal bonds is just a good bet, regardless of your immediate inflation view. The most obvious one I wrote about back in March 2020 in “The Big Bet of 10-year Breakevens at 0.94%,” and I’ve also written generally about why you might want to be long inflation-linked bonds even if the current level of implied inflation (aka ‘breakevens’) is near to fair on the basis of your own view about the trajectory of inflation (see “A Guess at the Value of Long Inflation Tails” as an example).

But the times when just being long TIPS instead of nominals…or being long breakevens or inflation swaps if you do it as a leveraged play…is advantageous are not limited to unusual circumstances. TIPS also have tended to be systematically cheap over long periods of time, which I’ve also documented. Another way to consider the same question is to ask, “if I bought 10-year breakevens when they were at a particular level, how would I have done historically?” Or, equivalently, “if I had switched into 10y TIPS, instead of 10y Treasuries, when the spread was at a particular level, how much would I have out- or under-performed historically?” The chart below answers that question.

I went back to February 1998. For each of 6,453 days (ending in June 2023 since I had to look forward 6 months) I considered the starting 10-year breakeven rate and calculated the return to being long that breakeven over the next 6 months.[1] That return is dependent on the relative yields of the different securities, how those yields (and hence the breakeven) changed over time, and how actual inflation developed. It’s worth pointing out that this time period, core inflation was below 3% for 90% of the time. Ergo, you wouldn’t expect to have lots of big wins because of inflation surprise, although of course toward the end of the historical period you did.

The chart shows for each bin (I threw all 58 days with 10-year breakevens lower than 0.75% into the same bucket, which turned out to be equal to the number of days in the 2.75%-3.00% bucket) what the average 6-month return was to being long 10-year breakevens along with the 10th percentile and 90th percentile. So you can see that on average, you didn’t lose money being long breakevens anywhere under 2.50%, despite the fact that inflation throughout this period was very low. That’s a function of what I said before, that TIPS in general were cheap throughout this period. And if you bought breakevens (or switched into TIPS) any time that the breakeven was below 1.5%, you had a 90% or better chance of winning.

Naturally, it shouldn’t be a surprise that if you buy breakevens at a cheap level – as with any asset – you stand a better chance of winning than if you bought it at a dear level. What is a little more of a surprise is that there hasn’t historically been very much pain, on average, to being long breakevens even when they are high. In fact, unless you bought breakevens above 2.75% – basically, one event in 2022 – you had at least a 40% chance of winning your bet (10y TIPS outperforming).

This isn’t to say that there aren’t a lot of ways to lose, trading or investing in TIPS. Like any other investment, they can lose money and in 2022-2023 being naked long TIPS was almost as painful as being naked long any other fixed-income instrument. Almost. You did lots better than if you’d owned nominal Treasuries through the same episode!

[1] I used the Bloomberg US 10 year Breakeven Inflation Index, which is a total return index (BXIIUB10 Index on Bloomberg), from its inception in 2006; prior to that I used Enduring Investments calculations which utilized roughly the same methodology.

2024 Balance of Risks

I am a risk manager, both literally and figuratively. Literally, since whether it is with our own funds and strategies or allocations for individual investor clients, or with my trading book back when I worked on Wall Street, the hard constraints are always capital, capital, and capital and so managing risk is part of how you make sure you don’t lose that capital. But also figuratively – my natural disposition is conservative, which is why I am a bond guy (concerned with getting my original investment back at par, at the end) rather than an equity guy (filled with dreams of a 10-bagger because I’m the first guy to figure out that Blockbuster Video is going to revolutionize video rental, and not so worried about how it will vanish almost overnight to Netflix).

So when I look at the investing landscape, I’m generally not focusing very much on ‘what I think is going to happen’; rather I spend more time thinking about the range of possible things that might happen, and their relative likelihoods. In theory, all rational investors do this but the markets do not trade like it. For example, currently Crude Oil trading at $72.60 does not seem to put any weight on the possibility of a hot war in the Middle East that could abruptly spike prices to $125/bbl or more. That’s not a prediction there will be a conflict that disrupts oil production or distribution (which, since there’s already a conflict – even though it hasn’t impacted oil production and only marginally impacted distribution – doesn’t seem like the sort of tiny-risk possibility we can ignore), but merely an observation. If you think there’s even a 10% chance that oil spikes $50/bbl, it would be worth $5/bbl. “But Mike,” you say, “maybe that’s already in the price and but for that possibility oil would be $5 lower?” Well, the risk manager in me looks for confirmation that the market is at least a little nervous, and with the Oil VIX trading at its long-term average and well below the average of the post-2020 spike it strikes me as hard to characterize the energy markets as ‘nervous.’

Anyway, this is why I dislike year-end ‘outlook’ pieces and why when I forecast CPI for a year or two out I almost always focus on a range of probable outcomes rather than a point estimate.[1] Honestly we should all do this, but not enough people have studied enough statistics to understand the significance of the error bars. If you have an experimental mean, and a nice large error bar, it signifies that you can’t reject the possibility that the true mean is anywhere in the range covered by the error bar. And that’s why, when someone introduces a new rent index that supposedly is more current but by their own admission has 15 times the standard error…I ignore it.

Enough of the preliminaries. Let me get on with this. Here are my thoughts about the balance of risks for just a few important items:

Interest rates: balance of risks is clearly higher. This was even more true at the end of the year. But with 10-year rates at 4.11%, down from 5% in October, keep in mind that two ways to get lower interest rates are already priced in: the short end of the curve reflects expectations (despite Fed officials’ protestations to the contrary) of roughly 150bps of cuts in the overnight policy rate this year, and the long end reflects inflation expectations of only 2.27% inflation over the next 5 years and only 2.30% inflation over the next decade. On top of this, consider that with the trade deficit declining but the budget deficit not declining, more of the budget deficit will have to be funded from domestic saving – and the Fed is still shrinking its balance sheet, so it is pushing in the opposite direction. The balance of risks in the bond market is to higher rates.

Stock market: balance of risks is lower, with the caveat that the picture is much better if looking at the market ex-the ‘Magnificent 7’ hot stocks (Apple, Nvidia, Meta, Tesla, Amazon, Microsoft, and Google). The S&P currently has a P/E of 21.4 and is up 24% since the end of 2022. The S&P ex-Mag7 has a P/E of 18.4 and is up 11% since the end of 2022. The Magnificent 7 themselves have a P/E of 39.5 and are up 110% over the last year.

The overall market P/E looks not-too-bad, until you remember that this is only because profit margins are currently only just a bit below at least 30-year highs (and probably lots longer – this is as far back as Bloomberg has trailing-12-months margins). The balance of risks is definitely for lower margins, which means lower earnings, which means the same equity prices would represent higher P/Es. Oh, and whatever happened to those people saying that the high equity prices were due to the really low interest rates? Haven’t heard from them in a while.

Where I have clients who are long equities, they’re long equal-weight indices so as to lessen exposure to the Magnificent 7. But even if those stocks were the only ones overvalued, it’s not reasonable to think that they can come back to earth and not bring down the rest of the market. If Apple, Nvidia, Meta, and Microsoft drop 30%, the rest of the market isn’t going to go up. However, if such a thing were to happen the market outside of the Mag 7 could feasibly eventually get to looking cheap.

Credit spreads: balance of risks is wider, with the 10-year Baa credit spread near 30-year lows. Really, how low does this go? And the tails are obviously one-way.

So I’ve said the balance of risks favor higher interest rates, wider credit spreads, lower corporate margins, and lower equity prices. It’s also useful to think about where the risks are in my risk assessments. If we get lower interest rates, instead of higher, then it’s very likely due to the economy being a lot weaker than it currently is, and the Fed ends up having to ease more than 150bps in 2024. That seems unlikely to me, but if it happens then notice that probably also means that credit spreads will widen and corporate margins, earnings, and stock prices decline. So, if you’re bullish on bonds and stocks, it seems to me you’re taking a dangerously narrow path. The balance of risks to me look bearish on both sides of that, but the bullish outcome for bonds implies (I think) a bearish outcome for stocks. It’s difficult for me to see an environment with appreciably higher stocks and bonds, unless the Fed eases aggressively without any economic weakness. So that’s your implied bet.

On the other hand, being bearish both stocks and bonds doesn’t carry such a narrow path risk. Unless the Fed eases despite a solid economy, It isn’t hard to envision an environment with lower stocks and bonds. Heck, we had just such an environment a few months ago, pre-‘pivot.’ It’s not a reach.

None of the preceding is a forecast. But investing and trading are about evaluating the range of risks, and trying to take positions with asymmetric risk-adjusted payoffs. In my opinion, long-only investors should be playing short on the yield curve (and going up credit, and inflation-linked rather than nominal) and anti- cap-weighting their stock holdings.

That’s as close to an outlook piece as I am doing this year. Have fun.

[1] In the last few years, I’ve started putting a point estimate for CPI in my Quarterly Inflation Outlook, but I also report what I see as the 1 standard deviation range so I can indicate the skewness of the risks in my view.

How Higher Rates Cause Big Changes in the Bond Contract

Two weeks ago I pointed out one of the effects of higher interest rates is that leveraged return strategies get swiftly worse as rates rise. Today, I want to talk about another result of higher interest rates which is, to me, much more fun and exciting. It involves the Treasury Bond cash-futures basis.

I know, that doesn’t sound so interesting. For many years, it hasn’t been. But lately, it has gotten really, really interesting – and institutional fixed-income investors and hedgers need to know that one of the major effects of higher interest rates is that it makes the bond contract negatively convex, not to mention that right now the bond contract also looks wildly expensive.

Some background is required. The CBOT bond futures contract (and the other bond contracts such as the Ultra, the (10y) Note, the 5y, and the 2y) calls for the physical delivery of actual Treasury securities, rather than cash settlement. Right now, thanks to ‘robust’ Treasury issuance patterns, there are an amazing 54 securities that are deliverable against the December bond futures contract. The futures contract short may deliver any of these bonds to satisfy his obligations under the contract, and may do so any time within the delivery month.

Now, if we just said the short can deliver any bond, the short would obviously choose the lowest-priced bond. The lowest-coupon bond is almost always going to be the lowest-priced; right now, the 1.125%-8/15/2040 sports a dollar price of 55.5.[1] But if we already know what bond is going to be deliverable, and it’s always the optimal bond to deliver, then the futures contract is just a forward contract on that bond, and it becomes very uninteresting (not to mention that liquidity of that one bond will determine the liquidity of the contract). So, when the contract was developed the CBOT determined that when the bond is delivered it will be priced, relative to the contract’s price, according to a conversion factor that is meant to put all of the bonds on more or less similar footing.[2] The price that the contract short gets paid when he delivers that particular bond is determined by the futures price, the factor, and the accrued interest on the delivery date…and not the price of the bond in the market.

Because the conversion factor is fixed, but the bonds all have different durations, which bond is cheapest-to-deliver (“CTD”) changes as interest rates change. When interest rates fall, short-duration bonds rise in price more slowly than long-duration bonds and so they get relatively cheaper and tend to become CTD. When interest rates rise, long-duration bonds fall in price more quickly than short-duration bonds and so tend to become CTD in that circumstance. And here’s the rub: when interest rates were well below the 6% “contract rate”, the CTD bond got locked at the shortest-duration deliverable, which also usually happened to be the shortest-maturity deliverable, because that bond got cheaper and cheaper and cheaper as the market rose and rose and rose. The consequence is that the bond contract, as mentioned earlier, eventually did become just a forward contract on the CTD (and a short-duration CTD at that), which meant that the volatility of the futures contract was lower, the implied volatility of futures options was lower, and the price of the futures contract was uninteresting to arbitrageurs because it was very obviously the forward price of the CTD. And this situation persisted for decades. The last time the bond and 10-year note yielded as much as 6% (which is where all of the excitement is maximized, since after all the conversion factor is designed to make them all more or less interchangeable at that level) was 2000. [Coincidentally or not, that was right about the time I stopped being exclusively a fixed-income relative value strategist/salesman and started trading options, and then inflation.]

So, now the long bond yields 4.96% and the deliverable bonds in the December bond contract basket have yields between 5.03% and 5.22%. This starts to get interesting. As of today, the CTD bond is the 4.75%-Feb 15, 2041. If you buy that bond and sell the contract,[3] then the worst possible case for you is that you deliver that bond into the contract and lose roughly 12/32nds after carry.

However.

Because you are short the futures contract, you can deliver whatever bond is most-advantageous to you at the time you elect to deliver. If any other bond is cheaper than the 4.75s-Feb41, then you buy that bond, sell the Feb41s, and deliver. And obviously, that’s a gain to you. And you can make that switch as often as you like, up until delivery.

Can you predict approximately when the bonds will switch? Sure, because we know the bonds’ durations we can estimate the CTD – and the value of switching – for normal yield curve shifts. While the steepening and flattening of the deliverable curve also matter, remember that anything that adds volatility to the potential switch point adds value to you, the futures short. Here is, roughly, the expected basis at delivery of that Feb41 bond.

Now isn’t this interesting? If the bond market rallies, then we know that shorter-duration bonds will become CTD, pushing the Feb 41s out. And if the bond market sells off, then we know that longer-duration bonds will replace the Feb 41s as CTD. Notice that this looks something like an options strangle? That’s because it essentially is. You own a strangle, and you’re paying 12/32nds for that strangle. (Spoiler alert: you can sell a comparable options position in the market for roughly 28/32nds, making the basis of that bond about half a point cheap, or equivalently the futures are about half a point rich.

Okay – if you’re not a fixed-income relative value strategist…and let’s face it, they’re a dying breed…then why do you care?

If you’re a plain old bond portfolio manager, you may use futures as a hedge for your position; you might use futures to get long bonds quickly without having to buy actual bonds, or because you aren’t allowed to repo your physical bonds but you can get some of the same benefits by buying the futures contract. You might buy options on futures to get convexity on your position, or to hedge the negative convexity in your mortgage portfolio.

Well guess what! None of that stuff works the same way it did 15 months ago!

Because longer-duration bonds are CTD now, the contract has more volatility. Which means the options on those futures have more implied volatility. Also, the bond contract is no longer guaranteed to be within a tick of fair value because the CTD is locked. When I worked for JP Morgan’s futures group, we thought if the futures contract got 6 ticks rich or cheap it was exciting. Well, we’re looking at a futures contract that’s a half-point mispriced![4]

Finally – as I said, the bond contract now has negative convexity, which means that when you are long the contract you will underperform in a rally and underperform in a selloff (while earning the net basis of 12 ticks, in a best case). Because when you own the bond contract you have the opposite position I’ve illustrated above: you’re short a strangle. If you’re long the contract then as the market sells off the bond contract will go down faster and faster as it tracks longer and longer duration deliverables. And if the market rallies, the contract will rise slower and slower as it tracks shorter duration deliverables. The implication is that especially because the bond contract is rich, it is great as a hedge for long cash positions at the moment, and a pretty bad hedge for short positions. And it’s great to hedge long mortgage positions, since when you sell the contract you also pick up some convexity rather than adding to your short-convexity position.

This all sounds, I’m sure, very “inside baseball.” And it is, because most of the people who used to trade this stuff and understood it are retired, have moved to corner offices, or are old inflation guys who just wonder why we don’t have a deliverable TIPS contract. But just as with my article two weeks ago, it’s something that I think it important to point out. We’re so obsessed with the ‘macro’ implications of higher rates, we stand to miss some of the really important implications on the ‘micro’ side of things!

[1] I’m using decimals to make this more accessible to non-bond folks, but we all know that this really means 55-16.

[2] The conversion factor is the answer to the question, “what would the price of this bond be if, on the first day of the delivery month, it were to yield exactly 6% to maturity”? So the aforementioned 1-1/8 of Aug-40s have a conversion factor into the December contract of 0.4938 while the 3-7/8 of Aug-40 has a conversion factor of 0.7794.

[3] I am abstracting here from the more technical nuances of how one weights a bond basis trade, again for brevity and accessibility.

[4] There’s a big caveat here in that the yield curve dynamics in my model for the shape of the deliverable bond yield curve are out-of-date, as I haven’t used this model in years…so the contract might be anywhere from 10 ticks to 20 ticks rich. But it’s rich!

We Are All Bond Traders Now

When I started working in the financial markets, bond traders were the cool kids. The equity guys drove Maseratis and acted like buffoons, but the bond guys drove sensible style like Mercedes and cared about things like deficits and credit. The authoritative word on this subject came from the book Liar’s Poker by Michael Lewis, about 1980s Salomon Brothers, where the trainees dreaded being assigned to do Equities in Dallas.

Back then, equities guys worried about earnings, the quality of management and the balance sheet, and the really boring ones worried about a margin of safety and investing at the right price. That seems Victorian now, but I guess so does the idea that sober institutions should only own bonds.

Down the list of concerns, but still on it, were interest rates. Ol’ Marty Zweig used to have a commercial in which he said “if you can spot meaningful changes (not just zig-zags) in interest rates and momentum, you’ll be mostly in stocks during major advances and out during major declines.” The reason that interest rates matter at all to a stock jockey is that the present value of any series of cash flows, such as dividends, depends on the interest rate used to discount those cash flows.

In general, if the discount curve (yield curve) is flat, then the present value of a series of cash flows is the sum of the present values of each cash flow:

…where r is the interest rate.

As a special case, if all of the cash flows are equal and go on forever, then we have a perpetuity where PV = CF/r. Note also that if all of the cash flows have the same real value and are only adjusted for inflation, and the denominator is a real interest rate, then you get the same answer to the perpetuity problem.[1]

I should say right now that the point of this article is not to go into the derivation of the Gordon Growth Model, or argue about how you should price something where the growth rate is above the discount rate, or how you treat negative rates in a way that doesn’t make one’s head explode. The point of this article is merely to demonstrate how the sensitivity of that present value to the numerator and the denominator changes when interest rates change.

The sensitivity to the numerator is easy. PV is linear with respect to CF. That is, if the cash flow increases $1 per period, then the present value of the whole series increases the same amount regardless of whether we are increasing from $2 to $3 or $200 to $201. In the table below, the left two columns represent the value of a $5 perpetuity versus a $6 perpetuity at various interest rates; the right two columns represents the value of a $101 perpetuity versus a $102 perpetuity. You can see that in each case, the value of the perpetuity increases the same amount going left to right in the green columns as it does going left to right in the blue columns. For example, if the interest rate is 5%, then an increase in $1 increases the total value by $20 whether it’s from $5 to $6 or $100 to $101.

However, the effect of the same-sized movement in the denominator is very different. We call this sensitivity to interest rates duration, and in one of its forms that sensitivity is defined as the change in the price for a 1% change in the yield.[2] Moving from 1% to 2% cuts the value of the annuity (in every case) by 50%, but moving from 4% to 5% cuts the value by only 20%.

What this means is that if interest rates are low, you care a great deal about the interest rate. Any change to your numerator is easily wiped out by a small change in the interest rate you are discounting at. But when interest rates are higher, this is less important and you can focus more on the numerator. Of course, in this case we are assuming the numerator does not change, but suppose it does? The importance of a change in the numerator depends not on the numerator, but on the denominator. And for a given numerator, any change in the denominator gets more important at low rates.

So, where am I going with this?

Let’s think about the stock market. For many years now, the stock market has acted as if what the Fed does is far more important than what the businesses themselves do. And you know what? Investors were probably being rational by doing so. At low interest rates, the change in the discount rate was far more important – especially for companies that don’t pay dividends, so they’re valued on some future harvest far in the future – than changes in company fortunes.

However, as interest rates rise this becomes less true. As interest rates rise, investors should start to care more and more about company developments. I don’t know that there is any magic about the 5% crossover that I have in that chart (the y-axis, by the way, is logarithmic because otherwise the orange line gets vertical as we get to the left edge!). But it suggests to me that stock-picking when interest rates are low is probably pointless, while stock-picking when interest rates are higher is probably fairly valuable. What does an earnings miss mean when interest rates are at zero? Much less than missing on the Fed call. But at 5%, the earnings miss is a big deal.

Perhaps this article, then, is mistitled. It isn’t that we are all bond traders now. It’s that, until recently, we all were bond traders…but this is less and less true.

And it is more and more true that forecasts of weak earnings growth for this year and next – are much more important than the same forecasts would have been, two years ago.

But the bond traders are still the cool kids.

[1] I should also note that r > 0, which is something we never had to say in the past. In nominal space, anyway, it would be an absurdity to have a perpetually negative interest rate, implying that future cash flows are worth more and more…and the perpetuity has infinite value.

[2] Purists will note that the duration at 2% is neither the change in value from 1% to 2% nor from 2% to 3%, but rather the instantaneous change at 2%, scaled by 100bps. But again, I’m not trying to get to fine bond math here and just trying to make a bigger point.