Archive

How Higher Rates Cause Big Changes in the Bond Contract

Two weeks ago I pointed out one of the effects of higher interest rates is that leveraged return strategies get swiftly worse as rates rise. Today, I want to talk about another result of higher interest rates which is, to me, much more fun and exciting. It involves the Treasury Bond cash-futures basis.

I know, that doesn’t sound so interesting. For many years, it hasn’t been. But lately, it has gotten really, really interesting – and institutional fixed-income investors and hedgers need to know that one of the major effects of higher interest rates is that it makes the bond contract negatively convex, not to mention that right now the bond contract also looks wildly expensive.

Some background is required. The CBOT bond futures contract (and the other bond contracts such as the Ultra, the (10y) Note, the 5y, and the 2y) calls for the physical delivery of actual Treasury securities, rather than cash settlement. Right now, thanks to ‘robust’ Treasury issuance patterns, there are an amazing 54 securities that are deliverable against the December bond futures contract. The futures contract short may deliver any of these bonds to satisfy his obligations under the contract, and may do so any time within the delivery month.

Now, if we just said the short can deliver any bond, the short would obviously choose the lowest-priced bond. The lowest-coupon bond is almost always going to be the lowest-priced; right now, the 1.125%-8/15/2040 sports a dollar price of 55.5.[1] But if we already know what bond is going to be deliverable, and it’s always the optimal bond to deliver, then the futures contract is just a forward contract on that bond, and it becomes very uninteresting (not to mention that liquidity of that one bond will determine the liquidity of the contract). So, when the contract was developed the CBOT determined that when the bond is delivered it will be priced, relative to the contract’s price, according to a conversion factor that is meant to put all of the bonds on more or less similar footing.[2] The price that the contract short gets paid when he delivers that particular bond is determined by the futures price, the factor, and the accrued interest on the delivery date…and not the price of the bond in the market.

Because the conversion factor is fixed, but the bonds all have different durations, which bond is cheapest-to-deliver (“CTD”) changes as interest rates change. When interest rates fall, short-duration bonds rise in price more slowly than long-duration bonds and so they get relatively cheaper and tend to become CTD. When interest rates rise, long-duration bonds fall in price more quickly than short-duration bonds and so tend to become CTD in that circumstance. And here’s the rub: when interest rates were well below the 6% “contract rate”, the CTD bond got locked at the shortest-duration deliverable, which also usually happened to be the shortest-maturity deliverable, because that bond got cheaper and cheaper and cheaper as the market rose and rose and rose. The consequence is that the bond contract, as mentioned earlier, eventually did become just a forward contract on the CTD (and a short-duration CTD at that), which meant that the volatility of the futures contract was lower, the implied volatility of futures options was lower, and the price of the futures contract was uninteresting to arbitrageurs because it was very obviously the forward price of the CTD. And this situation persisted for decades. The last time the bond and 10-year note yielded as much as 6% (which is where all of the excitement is maximized, since after all the conversion factor is designed to make them all more or less interchangeable at that level) was 2000. [Coincidentally or not, that was right about the time I stopped being exclusively a fixed-income relative value strategist/salesman and started trading options, and then inflation.]

So, now the long bond yields 4.96% and the deliverable bonds in the December bond contract basket have yields between 5.03% and 5.22%. This starts to get interesting. As of today, the CTD bond is the 4.75%-Feb 15, 2041. If you buy that bond and sell the contract,[3] then the worst possible case for you is that you deliver that bond into the contract and lose roughly 12/32nds after carry.

However.

Because you are short the futures contract, you can deliver whatever bond is most-advantageous to you at the time you elect to deliver. If any other bond is cheaper than the 4.75s-Feb41, then you buy that bond, sell the Feb41s, and deliver. And obviously, that’s a gain to you. And you can make that switch as often as you like, up until delivery.

Can you predict approximately when the bonds will switch? Sure, because we know the bonds’ durations we can estimate the CTD – and the value of switching – for normal yield curve shifts. While the steepening and flattening of the deliverable curve also matter, remember that anything that adds volatility to the potential switch point adds value to you, the futures short. Here is, roughly, the expected basis at delivery of that Feb41 bond.

Now isn’t this interesting? If the bond market rallies, then we know that shorter-duration bonds will become CTD, pushing the Feb 41s out. And if the bond market sells off, then we know that longer-duration bonds will replace the Feb 41s as CTD. Notice that this looks something like an options strangle? That’s because it essentially is. You own a strangle, and you’re paying 12/32nds for that strangle. (Spoiler alert: you can sell a comparable options position in the market for roughly 28/32nds, making the basis of that bond about half a point cheap, or equivalently the futures are about half a point rich.

Okay – if you’re not a fixed-income relative value strategist…and let’s face it, they’re a dying breed…then why do you care?

If you’re a plain old bond portfolio manager, you may use futures as a hedge for your position; you might use futures to get long bonds quickly without having to buy actual bonds, or because you aren’t allowed to repo your physical bonds but you can get some of the same benefits by buying the futures contract. You might buy options on futures to get convexity on your position, or to hedge the negative convexity in your mortgage portfolio.

Well guess what! None of that stuff works the same way it did 15 months ago!

Because longer-duration bonds are CTD now, the contract has more volatility. Which means the options on those futures have more implied volatility. Also, the bond contract is no longer guaranteed to be within a tick of fair value because the CTD is locked. When I worked for JP Morgan’s futures group, we thought if the futures contract got 6 ticks rich or cheap it was exciting. Well, we’re looking at a futures contract that’s a half-point mispriced![4]

Finally – as I said, the bond contract now has negative convexity, which means that when you are long the contract you will underperform in a rally and underperform in a selloff (while earning the net basis of 12 ticks, in a best case). Because when you own the bond contract you have the opposite position I’ve illustrated above: you’re short a strangle. If you’re long the contract then as the market sells off the bond contract will go down faster and faster as it tracks longer and longer duration deliverables. And if the market rallies, the contract will rise slower and slower as it tracks shorter duration deliverables. The implication is that especially because the bond contract is rich, it is great as a hedge for long cash positions at the moment, and a pretty bad hedge for short positions. And it’s great to hedge long mortgage positions, since when you sell the contract you also pick up some convexity rather than adding to your short-convexity position.

This all sounds, I’m sure, very “inside baseball.” And it is, because most of the people who used to trade this stuff and understood it are retired, have moved to corner offices, or are old inflation guys who just wonder why we don’t have a deliverable TIPS contract. But just as with my article two weeks ago, it’s something that I think it important to point out. We’re so obsessed with the ‘macro’ implications of higher rates, we stand to miss some of the really important implications on the ‘micro’ side of things!

[1] I’m using decimals to make this more accessible to non-bond folks, but we all know that this really means 55-16.

[2] The conversion factor is the answer to the question, “what would the price of this bond be if, on the first day of the delivery month, it were to yield exactly 6% to maturity”? So the aforementioned 1-1/8 of Aug-40s have a conversion factor into the December contract of 0.4938 while the 3-7/8 of Aug-40 has a conversion factor of 0.7794.

[3] I am abstracting here from the more technical nuances of how one weights a bond basis trade, again for brevity and accessibility.

[4] There’s a big caveat here in that the yield curve dynamics in my model for the shape of the deliverable bond yield curve are out-of-date, as I haven’t used this model in years…so the contract might be anywhere from 10 ticks to 20 ticks rich. But it’s rich!

Are Home Prices Too High?

There is an advantage to squatting in the same niche of the market for years, even decades. And that is that your brain will sometimes make connections on its own – connections that would not have occurred to your conscious mind, even if you were studying a particular question in what you thought was depth.

A case in point: yesterday I was re-writing an old piece I had on the value of real estate as a hedge, to make it a permanent page on my blog and a “How-To” on the Inflation Guy app. At one point, I’m illustrating how a homeowner might look at the “breakeven inflation” of homeownership, and my brain asked “I wonder how this has changed over time?”

So, I went back in the Shiller dataset and I calculated it. To save you time reading the other article, the basic notion is that a homeowner breaks even when the value of the home rises enough to cover the after-tax cost of interest, property taxes, and insurance. In what follows, I ignore taxes and insurance because those vary tremendously by locality, while interest does not. But you can assume that the “breakeven inflation” line for housing ought to be at least a little higher. In the chart below, I calculate the breakeven inflation assuming that mortgage rates are roughly equal to the long Treasury rate (which isn’t an awful assumption if there’s some upward slope to the yield curve, since the duration of a 30-year mortgage is a lot less than the duration of a 30-year Treasury), that a homeowner finances 80% of the purchase, pays taxes at the top marginal rate, and can fully deduct the amount of mortgage interest. I have a time series of the top marginal rate, but don’t have a good series for “normal down payment,” so this illustration could be more accurate if someone had those data. The series for inflation-linked bonds is the Enduring Investments imputed real yield series prior to 1997 (discussed in more detail here, but better and more realistic than other real yield research series). Here then are the breakeven inflation rates for bonds and homes.

It makes perfect sense that these should look similar. In both cases, the long bond rate plays an important role, because in both cases you are “borrowing” at the fixed rate to invest in something inflation-sensitive.

The intuition behind the relationship between the two lines makes sense as well. Prior to the administration of Ronald Wilson Reagan, the top income tax rate was 70% or above. Consequently, the value of the tax sheltering aspect of the mortgage interest made it much easier to break even on the housing investment than to invest in inflation bonds (had they existed). That’s why the red line is so much lower than the blue line, prior to 1982 (when the top marginal rate was cut to 50%) and why the lines converged further in 1986 or so (the top marginal rate dropped to 39% in 1987). The red line even moves above the blue line, indicating that it was becoming harder to break even owning a home, when the top rate dropped to 28%-31% for 1988-1992. Pretty cool, huh?

Now, this just looks at the amount of (housing) inflation of the purchase price of the home needed to break even. But the probability of realizing that level of housing inflation depends, of course, on (a) the overall level of inflation itself and (b) the level of home prices relative to some notion of fair value. This is similar to the way we look at probable equity returns: what earnings or dividends do we expect to receive (which is related to nominal economic growth), and what is the starting valuation level of equities (since we expect multiples to mean-revert over time). That brings me back to a chart that I have previously found disturbing, and that’s the relationship between median household income and median home prices. For decades, the median home price was about 3.4x median household income. Leading up to the housing bubble, that ballooned to over 5x…and we are back to about 5x now.

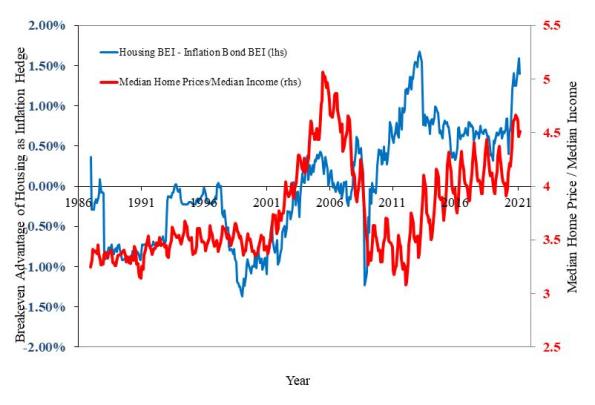

That’s the second part of the question, then – what is the starting valuation of housing? The answer right now is, it’s quite high. So are we in another housing bubble? To answer that, let’s compare the two pictures here. In the key chart below, the red line is the home price/income line from the chart above (and plotted on the right scale) while the blue line is the difference between the breakeven inflation for housing versus breakeven inflation in the bond market.

In 2006, the breakeven values were similar but home prices were very high, which means that you were better off taking the bird-in-the-hand of inflation bonds and not buying a home at those high prices. But today, the question is much more mixed. Yes, you are paying a high price for a home today; however, you also don’t need much inflation to break even. If home prices rise 1.5% less than general inflation, you will be indifferent between owning real estate and owning an inflation bond. Which means that, unlike in 2006-7, you aren’t betting on home prices continue to outpace inflation. It’s a closer call.

I can come up with a more quantitative answer than this, but my gut feeling is that home prices are somewhat rich, but not nearly as much so as in 2006-07, and not as rich as I had previously assumed. Moreover, while a home buyer today is clearly exposed to an increase in interest rates (which doesn’t affect the cash flow of the owner, but affects the value the home has to a future buyer), a home buyer will benefit from additional “tax shelter value” if income tax rates rise (as long as mortgage interest remains tax deductible!). And folks, I don’t know if taxes are going up, but that’s the direction I’d place my bets.

The Big Bet of 10-year Breakevens at 0.94%

It is rare for me to write two articles in one day, but one of them was the normal monthly CPI serial and this one is just really important!

I have been tweeting constantly, and telling all of our investors, and anyone else who will listen, that TIPS are being priced at levels that are, to use a technical term, kooky. With current median inflation around 2.9%, 10-year breakevens are being priced at 0.94%. That represents a real yield of about -0.23% for 10-year TIPS, and a nominal yield of about 0.71% for 10-year Treasuries. The difference in these two yields is 0.94%, and is approximately equal to the level of inflation at which you are indifferent to owning an inflation-linked bond and a nominal bond, if you are risk-neutral.

First, a reminder about how TIPS work. (This explanation will be somewhat simplified to abstract from interpolation methods, etc). TIPS, the U.S. Treasury’s version of inflation-linked bonds, are based on what is often called the Canadian model. A TIPS bond has a stated coupon rate, which does not change over the life of the bond and is paid semiannually. However, the principal amount on which the coupon is paid changes over time, so that the stated coupon rate is paid on a different principal amount each period. The bond’s final redemption amount is the greater of the original par amount or the inflation-adjusted principal amount.

Specifically, the principal amount changes each period based on the change in the Consumer Price All Urban Non-Seasonally Adjusted Index (CPURNSA), which is released monthly as part of the Bureau of Labor Statistics’ CPI report. The current principal value of a TIPS bond is equal to the original principal times the Index Ratio for the settlement date; the Index Ratio is the CPI index that applies to the coupon date divided by the CPI index that applied to the issue date.

To illustrate how TIPS work, consider the example of a bond in its final pay period. Suppose that when it was originally issued, the reference CPI for the bond’s dated date (that is, its Base CPI) was 158.43548. The reference CPI for its maturity date, it turns out, is 201.35500. The bond pays a stated 3.375% coupon. The two components to the final payment are as follows:

(1) Coupon Payment = Rate * DayCount * Stated Par * Index Ratio

= 3.375% * ½ * $1000 * (201.35500/158.43548)

= $21.45

(2) Principal Redemption = Stated Par * max [1, Index Ratio]

= $1000 * (201.35500/158.43548)

= $1,270.90

Notice that it is fairly easy to see how the construction of TIPS protects the real return of the asset. The Index Ratio of 201.35500/158.43548, or 1.27090, means that since this bond was issued, the total rise in the CPURNSA – that is, the aggregate rise in the price level – has been 27.09%. The coupon received has risen from 3.375% to an effective 4.2892%, a rise of 27.09%, and the bondholder has received a redemption of principal that is 27.09% higher than the original investment. In short, the investment produced a return stream that adjusted upwards (and downwards) with inflation, and then redeemed an amount of money that has the same purchasing power as the original investment. Clearly, this represents a real return very close to the original “real” coupon of 3.375%.

Now, there is an added bonus to the way TIPS are structured, and this is important to know at times when the market is starting to act like it is worried about deflation. No matter what happens to the price level, the bond will never pay back less than the original principal. So, in the example above the principal redemption was $1,270.90 for a bond issued at $1,000. But even if the price level was now 101.355, instead of 201.355, the bond would still pay $1,000 at maturity (plus coupon), even though prices have fallen since issuance. That’s why there is a “max[ ]” operator in the formula in (2) above.

So, back to our story.

If actual inflation comes in above the breakeven rate, then TIPS outperform nominals over the holding period. If actual inflation comes in below the breakeven rate, then TIPS underperform over the holding period. But, because of the floor, there is a limit to how much TIPS can underperform relative to nominals. However, there is no limit to how much TIPS can outperform nominals. This is illustrated below. For illustration, I’ve made the x-axis run from -4% compounded deflation over 10 years to 13% compounded inflation over 10 years. The IRR line for the nominal Treasury bond is obviously flat…it’s a fixed-rate bond. The IRR line for the TIPS bond looks like a call option struck near 0% inflation.

Note that, no matter how far I extend the x-axis to the left…no matter how much deflation we get…you will never beat TIPS by more than about 1% annualized. Never. On the other hand, if we get 3% inflation then you’ll lose by 2% per year. And it gets worse from there.

Because annualizing the effect makes this seem less dramatic, let’s look instead at the aggregate total return of TIPS and Treasuries. For simplicity, I’ve assumed that coupons are reinvested at the current yield to maturity of the 10-year note, which would obviously not be true at high levels of inflation but is in fact the simplifying assumption that the bond yield-to-maturity calculation makes.

So, if you own TIPS in a deflationary environment, you’ll underperform by about 10% over the next decade. Treasuries will return 7.3% nominal; TIPS will return -2.3% nominal. Unfortunate, but not disastrous. But if inflation is 8%, then your return on Treasuries will still be 7.3%, but TIPS will return 103%. Hmmm. Yay, your 10-year nominal Treasuries paid you back, plus 7.3% on top of that. But that $1073 is now worth…$497. Booo.

So the point here is that at these prices you should probably own TIPS even if you think we’re going to have deflation, unless you are really confident that you’re right. You are making a much bigger bet than you think you’re making.

COVID-19 in China is a Supply Shock to the World

The reaction of much of the financial media to the virtual shutdown of large swaths of Chinese production has been interesting. The initial reaction, not terribly surprising, was to shrug and say that the COVID-19 virus epidemic would probably not amount to much in the big scheme of things, and therefore no threat to economic growth (or, Heaven forbid, the markets. The mere suggestion that stocks might decline positively gives me the vapors!) Then this chart made the rounds on Friday…

…and suddenly, it seemed that maybe there was something worth being concerned about. Equity markets had a serious slump yesterday, but I’m not here to talk about whether this means it is time to buy TSLA (after all, isn’t it always time to buy Tesla? Or so they say), but to talk about the other common belief and that is that having China shuttered for the better part of a quarter is deflationary. My tweet on the subject was, surprisingly, one of my most-engaging posts in a very long time.

It has been so long since we have seen a supply shock that we have forgotten what they look like. China Inc shutting down is a supply shock. Supply shocks are inflationary, not disinflationary. Carry on.

— Michael Ashton (@inflation_guy) February 24, 2020

The reason this distinction between “supply shock” and “demand shock” is important is that the effects on prices are very different. The first stylistic depiction below shows a demand shock; the second shows a supply shock. In the first case, demand moves from D to D’ against a stable supply curve S; in the latter case, supply moves from S to S’ against a stable demand curve D.

Note that in both cases, the quantity demanded (Q axis) declines from c to d. Both (negative) demand and supply shocks are negative for growth. However, in the case of a negative demand shock, prices fall from a to b; in the case of a negative supply shock prices rise from a to b.

Of course, in this case there are both demand and supply shocks going on. China is, after all, a huge consumption engine (although a fraction of US consumption). So the growth picture is unambiguous: Chinese growth is going to be seriously impacted by the virtual shutdown of Wuhan and the surrounding province, as well as some ports and lots of other ancillary things that outsiders are not privy to. But what about the price picture? The demand shock is pushing prices down, and the supply shock is pushing them up. Which matters more?

The answer is not so neat and clean, but it is neater and cleaner than you think. Is China’s importance to the global economy more because of its consumption, as a destination for goods and services? Or is it more because of its production, as a source of goods and services? Well, in 2018 (source: Worldbank.org) China’s exports amounted to about $2.5trillion in USD, versus imports of $2.1trillion. So, as a first cut – if China completely vanished from global trade, it would amount to a net $400bln in lost supply. It is a supply shock.

When you look deeper, there is of course more complexity. Of China’s imports, about $239bln is petroleum. So if China vanished from global trade, it would be a demand shock in petroleum of $240bln (about 13mbpd, so huge), but a bigger supply shock on everything else, of $639bln. Again, it is a supply shock, at least ex-energy.

And even deeper, the picture is really interesting and really clear. From the same Worldbank source:

China is a huge net importer of raw goods (a large part of that is energy), roughly flat on intermediate goods, and a huge net exporter of consumer and capital goods. China Inc is an apt name – as a country, she takes in raw goods, processes them, and sells them. So, if China were to suddenly vanish, we would expect to see a major demand shock in raw materials and a major supply shock in finished goods.

China is a huge net importer of raw goods (a large part of that is energy), roughly flat on intermediate goods, and a huge net exporter of consumer and capital goods. China Inc is an apt name – as a country, she takes in raw goods, processes them, and sells them. So, if China were to suddenly vanish, we would expect to see a major demand shock in raw materials and a major supply shock in finished goods.

The effects naturally vary with the specific product. Some places we might expect to see significant price pressures are in pharmaceuticals, for example, where China is a critical source of active pharmaceutical ingredients and many drugs including about 80% of the US consumption of antibiotics. On the other hand, energy prices are under downward price pressure as are many industrial materials. Since these prices are most immediately visible (they are commodities, after all), it is natural for the knee-jerk reaction of investors to be “this is a demand shock.” Plus, as I said in the tweet, it has been a long time since we have seen a serious supply shock. But after the demand shock in raw goods (and possibly showing in PPI?), do not be surprised to see an impact on the prices of consumer goods especially if China remains shuttered for a long time. Interestingly, the inflation markets are semi-efficiently pricing this. The chart below is the 1-year inflation swap rate, after stripping out the energy effect (source: Enduring Investments). Overall it is too low – core inflation is already well above this level and likely to remain so – but the recent move has been to higher implied core inflation, not lower.

Now, if COVID-19 blossoms into a true global contagion that collapses demand in developed countries – especially in the US – then the answer is different and much more along the lines of a demand shock. But I also think that, even if this global health threat retreats, real damage has been done to the status of China as the world’s supplier. Although it is less sexy, less scary, and slower, de-globalization of trade (for example, the US repatriating pharmaceuticals production to the US, or other manufacturers pulling back supply chains to produce more in the NAFTA bloc) is also a supply shock.

Summary of My Post-CPI Tweets (September 2019)

Below is a summary of my post-CPI tweets. You can (and should!) follow me @inflation_guy. Or, sign up for email updates to my occasional articles here. Investors with interests in this area be sure to stop by Enduring Investments or Enduring Intellectual Properties (updated sites coming soon). Plus…buy my book about money and inflation. The title of the book is What’s Wrong with Money? The Biggest Bubble of All; order from Amazon here.

- CPI day again! And this time, we are coming off not one but TWO surprisingly-high core CPI prints of 0.29% for June and July respectively.

- But before I get into today’s report, I just want to let you know that I will be on TD Ameritrade Network @TDANetwork with @OJRenick at 9:15ET today. Tune in!

- And I’m going to start the walk-up to the number with two charts that I don’t often use on CPI day. The first shows the Atlanta Fed Wage Tracker, and illustrates that far from dead, the Phillips Curve is working fine: low unemployment has produced rising wages.

- The second chart, though, is why we haven’t seen the rising wage pressure in consumer prices yet. It shows that corporate margins are enormous. Businesses can pay somewhat higher wages and accept somewhat lower (but still ample) margins and refrain from price increases.

- This won’t last forever, but it’s the reason we haven’t felt the tariffs bite yet, too. Something to keep in mind.

- As for today: last month we saw core goods inflation at +0.4% y/y, the highest since 2013. I suspect that trend will continue for a bit longer, because tariffs DO matter. It’s just that they take longer to wash through to consumer prices than we think.

- In general, last month’s rise was mostly surprising because it was fairly broad-based. Nothing really weird, although the sustainability of retracements in apparel/hospital services/lodging away from home may be questioned.

- In fact, the oddest thing about last month’s figure is that “Other Goods and Services” jumped 0.52% m/m. OGaS is a jumble of stuff so it’s unusual to see it rising at that kind of rate. It’s only 3% of CPI, though.

- Consensus today is for a somewhat soft 0.2% on core. We drop off 0.08% from last August from the y/y numbers so the y/y will almost surely jump to at least 2.3% (unless there’s something weird in August seasonals). Good luck.

- Oh my.

- Well, it’s a soft 0.3% on core, at 0.26% m/m, but that’s the third 0.3% print in a row. The fact that none of them was actually as high as 0.3% is not terribly soothing.

- y/y core goes to 2.4% (actually 2.39%), rather than the 2.3% expected. Again, oh my.

- Last 12 core CPIs.

- Subcomponents trickling in but y/y core goods up to +0.8% y/y. Maybe those tariffs are having an impact. But this seems too large to be JUST tariffs.

- Core services also rose, to 2.9% y/y. But that’s less alarming.

- A big piece of the core goods jump was in Used Cars and Trucks, +1.05% m/m and up to +2.08% y/y.

- The used cars figure isn’t out of line, though.

- Primary Rents at +0.23% (3.74% y/y from 3.84%) and OER at +0.22% (3.34% vs 3.37%) are actually slightly dampening influences from what they had been. The contribution from their y/y dropped and the overall y/y still went up more than expected.

- Between them, OER and Primary Rents are about 1/3 of CPI, so to have them decelerate and still see core rise…

- Lodging Away from Home -2.08% m/m…lightweight, but certainly not a cause of the upside surprise. But Pharmaceuticals rose 0.61% m/m, pushing y/y back to flat (chart).

- …and hospital services jumped 1.35% m/m to 2.13% y/y. So the Medical Care subindex rose 0.74% m/m, to 3.46% y/y from 2.57%. Boom.

- Biggest m/m jumps are Miscellaneous Personal Goods, Public Transportation, Footwear, Used Cars & Trucks, and Medical Care Svcs. Only the last two have much weight and we have already mentioned them.

- It is going to be VERY close as to whether Median CPI rounds up to 3.0% y/y. I have it at 0.23% m/m (right in line with core) and 2.94% y/y.

- It’s time to wonder whether this rise in inflation is “actually happening this time.” Core ex-shelter rose from 1.3% y/y to 1.7% y/y. That’s the highest since Feb 2013. To be fair, it wasn’t “actually happening that time.”

- To be honest, I’m having trouble finding disturbing outliers. And that’s what’s disturbing.

- Quick four pieces charts. Food & Energy

- Core goods. This is the scary part.

- But Core Services is also showing some buoyancy. Again, look at the core-ex-shelter chart I tweeted just a bit ago.

- Lastly, Rent of Shelter. Still not doing anything…

- Got to go to ‘makeup’ for the @TDANetwork hit (I don’t really get makeup), but last thought. Fed is expected to ease next week. I think they still will. But this sets up a REALLY INTERESTING debate at the FOMC.

- Growth is fading, and worse globally, but it’s still okay in the US. And inflation…it’s hard to not get concerned at least a little…so there’s a chance they DON’T ease. A small chance, but not negligible.

- That’s all for today! It was worth it!

My comment that the Fed might not ease got more heated reaction than I have seen in a while. Clearly, there are a lot of people who are basing their investment thesis on the Fed providing easy money. I suppose it is impolitic to point out that that is exactly one great reason the Fed should not ease, even though the market is pricing it in.

But let’s look at the Fed’s pickle (er, not sure I like that imagery but we’ll go with it). The last ease from the FOMC was positioned as a ‘risk management’ sort of ease, with the Fed wanting to get the first shot in against slowing growth. I am completely in agreement that growth is slowing, but there are plenty of people who don’t agree with that. Globally, growth looks plainly headed into (or is already in) recession territory, but US protectionism has preserved US growth relative to the rest of the world. Yes, that comes at a cost in inflation to the US consumer, but so far we’ve gotten the protection without the side effects. That might be changing.

If the Fed believes that the inflation bump is because of tariffs, and they believe that lower rates will stimulate growth (I don’t, but that’s a story for another day), then the right thing to do is to ignore the rise in prices and ease anyway. If they do ease, I suspect they will include some language about the current increase in prices being partly attributable to higher import costs due to tariffs, and so temporary. But I don’t think there’s a ton of evidence that the rise in core inflation is necessarily tied exclusively to tariffs. So let’s suppose that the Fed believes that tariffs are not causing the current rise in median inflation to about 3% and core inflation the highest since the crisis. Then, if in fact the last ease really was for risk management reasons, then what’s the argument to ease further? Risks have receded, growth looks if anything slightly better than it did at the last meeting, and inflation is higher and in something that looks disturbingly like an uptrend. And, there is the question about whether reminding the world that they are independent from the Administration is worth doing. I really don’t think this ease is a slam-dunk. The arguments in favor were always fairly weak, and the arguments against are getting stronger. Maybe they don’t want to surprise the market, but if you can’t surprise the market with both bonds and stocks near all-time highs then when can you surprise the market? And if the answer is “never,” then why even have a Federal Reserve? Just leave it to the market in the first place!

And I’d be okay with that.

What’s Bad About the Fed Put…and Does Powell Have One?

Note: Come hear me speak this month at the Taft-Hartley Benefits Summit in Las Vegas January 20-22, 2019. I will be speaking about “Pairing Liability Driven Investing (LDI) and Risk Management Techniques – How to Control Risk.” If you come to the event I’ll buy you a drink. As far as you know.

And now on with our irregularly-scheduled program.

And now on with our irregularly-scheduled program.

Have we re-set the “Fed put”?

The idea that the Fed is effectively underwriting the level of financial markets is one that originated with Greenspan and which has done enormous damage to markets since the notion first appeared in the late 1990s. Let’s review some history:

The original legislative mandate of the Fed (in 1913) was to “furnish an elastic currency,” and subsequent amendment (most notably in 1977) directed the Federal Open Market Committee to “maintain long run growth of the monetary and credit aggregates commensurate with the economy’s long run potential to increase production, so as to promote effectively the goals of maximum employment, stable prices and moderate long-term interest rates.” By directing that the Federal Reserve focus on monetary and credit aggregates, Congress clearly put the operation of monetary policy a step removed from the unhealthy manipulation of market prices.

The Trading Desk at the Federal Reserve Bank of New York conducts open market operations to make temporary as well as permanent additions to and subtractions from these aggregates by repoing, reversing, purchasing, or selling Treasury bonds, notes, and bills, but the price of these purchases has always been of secondary importance (at best) to the quantity, since the purpose is to make minor adjustments in the aggregates.

This operating procedure changed dramatically in the global financial crisis as the Fed made direct purchase of illiquid securities (notably in the case of the Bear Stearns bankruptcy) as well as intervening in other markets to set the price at a level other than the one the free market would have determined. But many observers forget that the original course change happened in the 1990s, when Alan Greenspan was Chairman of the FOMC. Throughout his tenure, Chairman Greenspan expressed opinions and evinced concern about the level of various markets, notably the stock market, and argued that the Fed’s interest in such matters was reasonable since the “wealth effect” impacted economic growth and inflation indirectly. Although he most-famously questioned whether the market was too high and possibly “irrationally exuberant” in 1996, the Greenspan Fed intervened on several occasions in a manner designed to arrest stock market declines. As a direct result of these interventions, investors became convinced that the Federal Reserve would not allow stock prices to decline significantly, a conviction that became known among investors as the “Greenspan Put.”

As with any interference in the price system, the Greenspan Put caused misallocation of resources as market prices did not truly reflect the price at which a willing buyer and a willing seller would exchange ownership of equity risks, since both buyer and seller assumed that the Federal Reserve was underwriting some of those risks. In my first (not very good) book Maestro, My Ass!, I included this chart illustrating one way to think about the inefficiencies created:

The “S” curve is essentially an efficient frontier of portfolios that offer the best returns for a given level of risk. The “D” curves are the portfolio preference curves; they are convex upwards because investors are risk-averse and require ever-increasing amounts of return to assume an extra quantum of risk. The D curve describes all portfolios where the investor is equally satisfied – all higher curves are of course preferred, because the investor would get a higher return for a given level of risk. Ordinarily, this investor would hold the portfolio at E, which is the highest curve he/she can achieve given his/her preferences. The investor would not hold portfolio Q, because that portfolio has more risk than the investor is willing to take for the level of expected return offered, and he/she can achieve a ‘better’ portfolio (higher curve) at E.

But suppose now that the Fed limits the downside risk of markets by providing a ‘put’ which effectively caps the risk at X. Then, this investor will in fact choose portfolio Q, because portfolio Q offers higher return at a similar risk to portfolio E. So the investor ends up owning more risky securities (or what would be risky securities in the absence of the Fed put) than he/she otherwise would, and fewer less-risky securities. More stocks, and fewer bonds, which raises the equilibrium level of equity prices until, essentially, the curve is flat beyond E because at any increment in return, for the same risk, an investor would slide to the right.

So what happened? The chart below shows a simple measure of expected equity real returns which incorporates mean reversion to long-term historical earnings multiples, compared to TIPS real yields (prior to 1997, we use Enduring Investments’ real yield series, which I write about here). Prior to 1987 (when Greenspan took office, and began to promulgate the idea that the Fed would always ride to the rescue), the median spread between equity expected returns and long-term real yields was about 3.38%. That’s not a bad estimate of the equity risk premium, and is pretty close to what theorists think equities ought to offer over time. Since 1997, however – and here it’s especially important to use median since we’ve had multiple booms and busts – the median is essentially zero. That is, the capital market line averages “flat.”

If this makes investors happy (because they’re on a higher indifference curve), then what’s the harm? Well, this put (a free put struck at “X”) is not costless even though the Fed is providing it for free. If the Fed could provide this without any negative consequences, then by all means they ought to because they can make everyone happier for free. But there is, of course, a cost to manipulating free markets (Socialists, take note). In this case the cost appears in misallocation of resources, as companies can finance themselves with overvalued equity…which leads to booms and busts, and the ultimate bearer of this cost is – as it always is – the citizenry.

In my mind, one of the major benefits that Chairman Powell brought to the Chairmanship of the Federal Reserve was that, since he is not an economist by training, he treated economic projections with healthy and reasonable skepticism rather than with the religious faith and conviction of previous Fed Chairs. I was a big fan of Powell (and I haven’t been a big fan of many Chairpersons) because I thought there was a decent chance that he would take the more reasonable position that the Fed should be as neutral as possible and do as little as possible, since after all it turns out that we collectively suck when it comes to our understanding of how the economy works and we are unlikely to improve in most cases on the free market outcome. When stocks started to show some volatility and begin to reprice late last year, his calculated insouciance was absolutely the right attitude – “what Fed put?” he seemed to be saying. Unfortunately, the cost of letting the market re-adjust is to let it fall a significant amount so that there is again an upward slope between E and Q, and moreover let it stay there.

The jury is out on whether Powell does in fact have a price level in mind, or if he merely has a level of volatility in mind – letting the market re-adjust in a calm and gentle way may be acceptable to him, with his desire to intervene only being triggered by a need to calm things rather than to re-inflate prices. I’m hopeful that is the case, and that on Friday he was just trying to slow the descent but not to arrest it. My concern is that while Powell is not an economist, he did have a long career in investment banking, private equity, and venture capital. That might mean that he respects the importance of free markets, but it also might mean that he tends to exaggerate the importance of high valuations. Again, I’m hopeful, and optimistic, on this point. But that translates to being less optimistic on equity prices, until something like the historical risk premium has been restored.

The Neatest Idea Ever for Reducing the Fed’s Balance Sheet

I mentioned a week and a half ago that I’d had a “really cool” idea that I had mentioned to a member of the Fed’s Open Market Desk, and I promised to write about it soon. “It’s an idea that would simultaneously be really helpful for investors and help the Fed reduce a balance sheet that they claim to be happy with but we all really know they wish they could reduce.” First, some background.

It is currently not possible to directly access any inflation index other than headline inflation (in any country that has inflation-linked bonds, aka ILBs). Yet, many of the concerns that people have do not involve general inflation, of the sort that describes increases in the cost of living and erodes real investment returns (hint – people should care, more than they do, about inflation), but about more precise exposures. For examples, many parents care greatly about the inflation in the price of college tuition, which is why we developed a college tuition inflation proxy hedge which S&P launched last year as the “S&P Target Tuition Inflation Index.” But so far, that’s really the only subcomponent you can easily access (or will, once someone launches an investment product tied to the index), and it is only an approximate hedge.

This lack has been apparent since literally the beginning. CPI inflation derivatives started trading in 2003 (I traded the first USCPI swap in the interbank broker market), and in February 2004 I gave a speech at a Barclays inflation conference promising that inflation components would be tradeable in five years.

I just didn’t say five years from when.

We’ve made little progress since then, although not for lack of trying. Wall Street can’t handle the “basis risks,” management of which are a bad use of capital for banks. Another possible approach involves mimicking the way that TIGRs (and CATS and LIONs), the precursors to the Treasury’s STRIPS program, allowed investors to access Treasury bonds in a zero coupon form even though the Treasury didn’t issue zero coupon bonds. With the TIGR program, Merrill Lynch would put normal Treasury bonds into a trust and then issue receipts that entitled the buyer to particular cash flows of that bond. The sum of all of the receipts equaled the bond, and the trust simply allowed Merrill to disperse the ownership of particular cash flows. In 1986, the Treasury wised up and realized that they could issue separate CUSIPs for each cash flow and make them naturally strippable, and TIGRs were no longer necessary.

A similar approach was used with CDOs (Collateralized Debt Obligations). A collection of corporate bonds was put into a trust[1], and certificates issued that entitled the buyer to the first X% of the cash flows, the next Y%, and so on until 100% of the cash flows were accounted for. Since the security at the top of the ‘waterfall’ got paid off first, it had a very good rating since even if some of the securities in the trust went bust, that wouldn’t affect the top tranche. The next tranche was lower-rated and higher-yielding, and so on. It turns out that with some (as it happens, somewhat heroic) assumptions about the lack of correlation of credit defaults, such a CDO would produce a very large AAA-rated piece, a somewhat smaller AA-rated piece, and only a small amount of sludge at the bottom.

So, in 2004 I thought “why don’t we do this for TIPS? Only the coupons would be tied to particular subcomponents. If I have 100% CPI, that’s really 42% housing, 3% Apparel, 9% Medical, and so on, adding up to 100%. We will call them ‘Barclays Real Accreting-Inflation Notes,’ or ‘BRAINs’, so that I can hear salespeople tell their clients that they need to get some BRAINs.” A chart of what that would look like appears below. Before reading onward, see if you can figure out why we never had BRAINs.

When I was discussing CDOs above, you may notice that the largest piece was the AAA piece, which was a really popular piece, and the sludge was a really small piece at the bottom. So the bank would find someone who would buy the sludge, and once they found someone who wanted that risk they could quickly put the rest of the structure together and sell the pieces that were in high-demand. But with BRAINs, the most valuable pieces were things like Education, and Medical Care…pretty small pieces, and the sludge was “Food and Beverages” or “Transportation” or, heaven forbid, “Other goods and services.” When you create this structure, you first need to find someone who wants to buy a bunch of big boring pieces so you can sell the small exciting pieces. That’s a lot harder. And if you don’t do that, the bank ends up holding Recreation inflation, and they don’t really enjoy eating BRAINs. Even the zombie banks.

When I was discussing CDOs above, you may notice that the largest piece was the AAA piece, which was a really popular piece, and the sludge was a really small piece at the bottom. So the bank would find someone who would buy the sludge, and once they found someone who wanted that risk they could quickly put the rest of the structure together and sell the pieces that were in high-demand. But with BRAINs, the most valuable pieces were things like Education, and Medical Care…pretty small pieces, and the sludge was “Food and Beverages” or “Transportation” or, heaven forbid, “Other goods and services.” When you create this structure, you first need to find someone who wants to buy a bunch of big boring pieces so you can sell the small exciting pieces. That’s a lot harder. And if you don’t do that, the bank ends up holding Recreation inflation, and they don’t really enjoy eating BRAINs. Even the zombie banks.

Now we get to the really cool part.

So the Fed holds about $115.6 billion TIPS, along with trillions of other Treasury securities. And they really can’t sell these securities to reduce their balance sheet, because it would completely crater the market. Although the Fed makes brave noises about how they know they can sell these securities and it really wouldn’t hurt the market, they just have decided they don’t want to…we all know that’s baloney. The whole reason that no one really objected to QE2 and QE3 was that the Fed said it was only temporary, after all…

So here’s the idea. The Fed can’t sell $115bln of TIPS because it would crush the market. But they could easily sell $115bln of BRAINs (I guess Barclays wouldn’t be involved, which is sad, because the Fed as issuer makes this FRAINs, which makes no sense), and if they ended up holding “Other Goods and Services” would they really care? The basis risk that a bank hates is nothing to the Fed, and the Fed need hold no capital against the tracking error. But if they were able to distribute, say, 60% of these securities they would have shrunk the balance sheet by about $70 billion…and not only would this probably not affect the TIPS market – Apparel inflation isn’t really a good substitute for headline CPI – it would likely have the large positive effect of jump-starting a really important market: the market for inflation subcomponents.

And all I ask is a single basis point for the idea!

[1] This was eventually done through derivatives with no explicit trust needed…and I mean that in the totally ironic way that you could read it.

Alternative Risk Premia in Inflation Markets

I’m going to wade into the question of ‘alternative risk premia’ today, and discuss how this applies to markets where I ply my trade.

When people talk about ‘alternative risk premia,’ they mean one of two things. They’re sort of the same thing, but the former meaning is more precise.

- A security’s return consists of market beta (whatever that means – it is a little more complex than it sounds) and ‘alpha’, which is the return not explained by the market beta. If rx is the security return and rm is the market return, classically alpha is

The problem is that most of that ‘alpha’ isn’t really alpha but results from model under-specification. For example, thanks to Fama and French we have known for a long time that small cap stocks tend to add “extra” return that is not explained by their betas. But that isn’t alpha – it is a beta exposure to another factor that wasn’t in the original model. Ergo, if “SMB” is how we designate the performance of small stocks minus big stocks, a better model is

The problem is that most of that ‘alpha’ isn’t really alpha but results from model under-specification. For example, thanks to Fama and French we have known for a long time that small cap stocks tend to add “extra” return that is not explained by their betas. But that isn’t alpha – it is a beta exposure to another factor that wasn’t in the original model. Ergo, if “SMB” is how we designate the performance of small stocks minus big stocks, a better model is Well, obviously it doesn’t stop there. But the ‘alpha’ that you find for your strategy/investments depends critically on what model you’re using and which factors – aka “alternative risk premia” – you’re including. At some level, we don’t really know whether alpha really exists, or whether systematic alpha just means that we haven’t identified all of the factors. But these days it is de rigeur to say “let’s pay very little in fees for market beta; pay small fees for easy-to-access risk premia that we proactively decide to add to the portfolio (overweighting value stocks, for example), pay higher fees for harder-to-access risk premia that we want, and pay a lot in fees for true alpha…but we don’t really think that exists.” Of course, in other people’s mouths (mostly marketers) “alternative risk premia that you should add to your portfolio” just means…

Well, obviously it doesn’t stop there. But the ‘alpha’ that you find for your strategy/investments depends critically on what model you’re using and which factors – aka “alternative risk premia” – you’re including. At some level, we don’t really know whether alpha really exists, or whether systematic alpha just means that we haven’t identified all of the factors. But these days it is de rigeur to say “let’s pay very little in fees for market beta; pay small fees for easy-to-access risk premia that we proactively decide to add to the portfolio (overweighting value stocks, for example), pay higher fees for harder-to-access risk premia that we want, and pay a lot in fees for true alpha…but we don’t really think that exists.” Of course, in other people’s mouths (mostly marketers) “alternative risk premia that you should add to your portfolio” just means… - Whatever secret sauce we’re peddling, which provides returns you can’t get elsewhere.

So there’s nothing really mysterious about the search for ‘alternative risk premia’, and they’re not at all new. Yesteryear’s search for alpha is the same as today’s search for ‘alternative risk premia’, but the manager who wants to earn a high fee needs to explain why he can add actual alpha over not just the market beta, but the explainable ‘alternative risk premia’. If your long-short equity fund is basically long small cap stocks and short a beta-weighted amount of large-cap stocks, you’re probably not going to get paid much.

For many years, I’ve been using the following schematic to explain why certain sources of alpha are more or less valuable than others. The question comes down to the source of alpha, after you have stripped out the explainable ‘alternative risk premia’.

As an investor, you want to figure out where this manager’s skill is coming from: is it from theoretical errors, such as when some guys in Chicago discovered that the bond futures contract price did not incorporate the value of delivery options that accrued to the contract short, and harvested alpha for the better part of two decades before that opportunity closed? Or is it because Joe the trader is really a great trader and just has the market’s number? You want more of the former, which have high information ratios, are very persistent…but don’t come around that much. You shouldn’t be very confident in the latter, which seem to be all over the place but don’t tend to last very long and are really hard to prove. (I’ve been waiting for a long time to see the approach to fees suggested here in a 2008 Financial Analysts’ Journal article implemented.)

I care about this distinction because in the markets I traffic in, there are significant dislocations and some big honking theoretical errors that appear from time to time. I should hasten to say that in what follows, I will mention some results for strategies that we have designed at Enduring Intellectual Properties and/or manage via Enduring Investments, but this article should not be construed as an offer to sell any security or fund nor a solicitation of an offer to buy any security or fund.

- Let’s start with something very simple. Here is a chart of the first-derivative of the CPI swaps curve – that is, the one-year inflation swap, x-years forward (so a 1y, 1y forward; a 1y, 2y forward; a 1y, 3y forward, and so on). In developed markets like LIBOR, not only is the curve itself smooth but the forwards derived from that curve are also smooth. But this is not the case with CPI swaps.[1]

- I’ve also documented in this column from time to time the fact that inflation markets exaggerate the importance of near-term carry, so that big rallies in energy prices not only affect near-term breakevens and inflation swaps but also long-dated breakevens and inflation swaps, even though energy prices are largely mean-reverting.

- We’ve in the past (although not in this column) identified times when the implied volatility of core inflation was actually larger than the implied volatility of nominal rates…which outcome, while possible, is pretty unlikely.

- Back in 2009, we spoke to investors about the fact that corporate inflation bonds (which are structured very differently than TIPS and so are hard to analyze) were so cheap that for a while you could assemble a portfolio of these bonds, hedge out the credit, and still realize a CPI+5% yield at time when similar-maturity TIPS were yielding CPI+1%.

- One of my favorite arbs available to retail investors was in 2012, when I-series savings bonds from the US Treasury sported yields nearly 2% above what was available to institutional investors in TIPS.

But aside from one-off trades, there are also systematic strategies. If a systematic strategy can be designed that produces excess returns both in- and out- of sample, it is at least worth asking whether there’s ‘alpha’ (or undiscovered/unexploited ‘alternative risk premia’) here. All three of the strategies below use only liquid markets – the first one, only commodity futures; the second one, only global sovereign inflation bonds; and the third one, only US TIPS and US nominal Treasuries. The first two are ‘long only’ strategies that systematically rebalance monthly and choose from the same securities that appear in the benchmark comparison. (Beyond that, this public post obviously needs to keep methods undisclosed!). And also, please note that past results are no indication of future returns! I am trying to make the general point that there are interesting risk factors/alphas here, and not the specific point about these strategies per se.

- Our Enduring Dynamic Commodity Index is illustrated below. It’s more volatile, but not lots more volatile: 17.3% standard deviation compared to 16.1% for the Bloomberg Commodity Index.

That’s the most-impressive looking chart, but that’s because it represents commodity markets that have lots of volatility and, therefore, offer lots of opportunities.

- Our Global Inflation Bond strategy is unlevered and uses only the bonds that are included in the Bloomberg-Barclays Global ILB index. It limits the allowable overweights on smaller markets so that it isn’t a “small market” effect that we are capturing here. According to the theory that drives the model, a significant part of any country’s domestic inflation is sourced globally and therefore not all of the price behavior of any given market is relevant to the cross-border decision. And that’s all I’m going to say about that.

- Finally, here is a simple strategy that is derived from a very simple model of the relationship between real and nominal Treasuries to conclude whether TIPS are appropriately priced. The performance is not outlandish, and there’s a 20% decline in the data, but there’s also only one strategy highlighted here – and it beats the HFR Global Hedge Fund Index.

I come not to bury other strategies but to praise them. There are good strategies in various markets that deliver ‘alternative risk premia’ in the first sense enumerated above, and it is a good thing that investors are extending their understanding beyond conventional beta as they assemble portfolios. I believe that there are also strategies in various markets which deliver ‘alternative risk premia’ that are harder to access because they require rarer expertise. Finally, I believe that there are strategies – but these are very rare, and getting rarer – which deliver true alpha that derives from theoretical errors or systematic imbalances. I think that as a source of a relatively unexploited ‘alternative risk premium’ and a potential source of unique alphas, the inflation and commodity markets still contain quite a few useful nuggets.

[1] I am not necessarily claiming that this can be exploited easily right now, but the curve has had such imperfections for more than a decade – and sometimes, it’s exploitable.

Inflation and Corporate Margins

On Monday I was on the TD Ameritrade Network with OJ Renick to talk about the recent inflation data (you can see the clip here), money velocity, the ‘oh darn’ inflation strike, etcetera. But Oliver, as is his wont, asked me a question that I realized I hadn’t previously addressed before in this blog, and that was about inflation pressure on corporate profit margins.

On the program I said, as I have before in this space, that inflation has a strong tendency to compress the price multiples attached to profits (the P/E), so that even if margins are sustained in inflationary times it doesn’t mean equity prices will be. As an owner of a private business who expects to make most of the return via dividends, you care mostly about margins; as an owner of a share of stock you also care about the price other people will pay for that share. And the evidence is fairly unambiguous that inflation inside of a 1%-3% range (approximately) tends to produce the highest multiples – implying of course that, outside of that range, multiples are lower and therefore stock prices tend to adjust when the economy moves to a new inflation regime.

But is inflation good or bad for margins? The answer is much more complex than you would think. Higher inflation might be good for margins, since wage inputs are sticky and therefore producers of consumer goods can likely raise prices for their products before their input prices rise. On the other hand, higher inflation might be bad for margins if a highly-competitive product market keeps sellers from adjusting consumer prices to fully keep up with inflation in commodities inputs.

Of course, business are very heterogeneous. For some businesses, inflation is good; for some, inflation is bad. (I find that few businesses really know all of the ways they might benefit or be hurt by inflation, since it has been so long since they had to worry about inflation high enough to affect financial ratios on the balance sheet and income statement, for example). But as a first pass:

| You may be exposed to inflation if… | You may benefit from inflation if… |

| You have large OPEB liabilities | You own significant intellectual property |

| You have a current (open) pension plan with employees still earning benefits, | You own significant amounts of real estate |

| …especially if the workforce is large relative to the retiree population, and young | You possess large ‘in the ground’ commodity reserves, especially precious or industrial metals |

| …especially if there is a COLA among plan benefits | You own long-dated fixed-price concessions |

| …especially if the pension fund assets are primarily invested in nominal investments such as stocks and bonds | You have a unionized workforce that operates under collectively-bargained fixed-price contracts with a certain term |

| You have fixed-price contracts with suppliers that have shorter terms than your fixed-price contracts with customers. | |

| You have significant “nominal” balance sheet assets, like cash or long-term receivables | |

| You have large liability reserves, e.g. for product liability |

So obviously there is some differentiation between companies in terms of which do better or worse with inflation, but what about the market in general? This is pretty messy to disentangle, and the following chart hints at why. It shows the Russell 1000 profit margin, in blue, versus core CPI, in red.

Focus on just the period since the crisis, and it appears that profit margins tighten when core inflation increases and vice-versa. But there are two recessions in this data where profits fell, and then core inflation fell afterwards, along with one expansion where margins rose along with inflation. But the causality here is hard to ferret out. How would lower margins lead to lower inflation? How would higher margins lead to higher inflation? What is really happening is that the recessions are causing both the decline in margins and the central bank response to lower interest rates in response to the recession is causing the decline in inflation. Moreover, the general level of inflation has been so low that it is hard to extract signal from the noise. A slightly longer series on profit margins for the S&P 500 companies, since it incorporates a higher-inflation period in the early 1990s, is somewhat more suggestive in that the general rise in margins (blue trend) seems to be coincident with the general decline in inflation (red line), but this is a long way from conclusive.

Bloomberg doesn’t have margin information for equity indices going back any further, but we can calculate a similar series from the NIPA accounts. The chart below shows corporate after-tax profits as a percentage of GDP, which is something like aggregate corporate profit margins.

And this chart shows…well, it doesn’t seem to show much of anything that would permit us to make a strong statement about profit margins. Over time, companies adapt to inflation regime at hand. The high inflation of the 1970s was very damaging for some companies and extremely bad for multiples, but businesses in aggregate managed to keep making money. There does seem to be a pretty clear trend since the mid-1980s towards higher profit margins and lower inflation, but these could both be the result of deregulation, followed by globalization trends. To drive the overall point home, here is a scatterplot showing the same data.

So the verdict is that inflation might be bad for profits as it transitions from lower inflation to higher inflation (we have one such episode, in 1965-1970, and arguably the opposite in 1990-1995), but that after the transition businesses successfully adapt to the new regime.

That’s good news if you’re bullish on stocks in this rising-inflation environment. You only get tattooed once by rising inflation, and that’s via the equity multiple. Inflation will still create winners and losers – not always easy to spot in advance – but business will find a way.

Nudge at Neptune

Okay, I get it. Your stockbroker is telling you not to worry about inflation: it’s really low, core inflation hasn’t been above 3% for two decades…and, anyway, the Fed is really trying to push it higher, he says, so if it goes up then that’s good too. Besides, some inflation isn’t necessarily bad for equities since many companies can raise end product prices faster than they have to adjust wages they pay their workers.[1] So why worry about something we haven’t seen in a while and isn’t necessarily that bad? Buy more FANG, baby!

Keep in mind that there is a very good chance that your stockbroker, if he or she is under 55 years old, has never seen an investing environment with inflation. Also keep in mind that the stories and scenes of wild excess on Wall Street don’t come from periods when equities are in a bear market. I’m just saying that there’s a reason to be at least mildly skeptical of your broker’s advice to own “100 minus your age” in stocks when you’re young, which morphs into advice to “owning more stocks since you’re likely to have a long retirement” when you get a bit older.

Many financial professionals are better-compensated, explicitly or implicitly, when stocks are going up. This means that even many of the honest ones, who have their clients’ best interests at heart, can’t help but enjoy it when the stock market rallies. Conversations with clients are easier when their accounts are going up in size every day and they feel flush. There’s a reason these folks didn’t go into selling life insurance. Selling life insurance is really hard – you have to talk every day to people and remind them that they’re going to die. I’d hate to be an insurance salesman.

And yet, I guess that’s sort of what I am.

Insurance is about managing risks. Frankly, investing should also be about managing risks – about keeping as much upside as you can, while maintaining an adequate margin of safety. Said another way, it’s about buying that insurance as cheaply as you can so that you don’t spend all of your money on insurance. That’s why diversification is such a powerful idea: owning 20 stocks, rather than 1 stock, gets you downside protection against idiosyncratic risks – essentially for free. Owning multiple asset classes is even more powerful, because the correlations between asset classes are generally lower than the correlations between stocks. Diversification works, and it’s free, so we do it.

So let’s talk about inflation protection. And to talk about inflation protection, I bring you…NASA.

How can we prevent an asteroid impact with Earth?

The key to preventing an impact is to find any potential threat as early as possible. With a couple of decades of warning, which would be possible for 100-meter-sized asteroids with a more capable detection network, several options are technically feasible for preventing an asteroid impact.

Deflecting an asteroid that is on an impact course with Earth requires changing the velocity of the object by less than an inch per second years in advance of the predicted impact.

Would it be possible to shoot down an asteroid that is about to impact Earth?

An asteroid on a trajectory to impact Earth could not be shot down in the last few minutes or even hours before impact. No known weapon system could stop the mass because of the velocity at which it travels – an average of 12 miles per second.

NASA is also in the business of risk mitigation, and actually their problem is similar to the investor’s problem: find protection, as cheaply as possible, that allows us to retain most of the upside. We can absolutely protect astronauts in space from degradation of their DNA from cosmic rays, with enough shielding. The problem is that the more shielding you add, the harder it is to go very far, very fast, in space. So NASA wants to find the cheapest way to have an effective cosmic ray shield. And, in the ‘planetary defense’ role for NASA, they understand that deflecting an asteroid from hitting the Earth is much, much easier if we do it very early. A nudge when a space rock is out at the orbit of Neptune is all it takes. But wait too long, and there is no way to prevent the devastating impact.

Yes, inflation works the same way.

The impact of inflation on a normal portfolio consisting of stocks and bonds is devastating. Rising inflation hurts bonds because interest rates rise, and it hurts stocks because multiples fall. There is no hiding behind diversification in a ’60-40’ portfolio when inflation rises. Other investments/assets/hedges need to be put into the mix. And when inflation is low, and “high” inflation is far away, it is inexpensive to protect against that portfolio impactor. I have written before about how low commodities prices are compared with equity prices, and in January I also wrote a piece about why the expected return to commodities is actually rising even as commodities go sideways.

TIPS breakevens are also reasonable. While 10-year breakevens have risen from 1.70% to 2.10% over the last 9 months or so, that’s still below current median inflation, and below where core inflation will be in a few months as the one-offs subside. And it’s still comfortably below where 10-year breaks have traded in normal times for the last 15 years (see chart, source Bloomberg).

It is true that there are not a lot of good ways for smaller investors to simply go long inflation. But you can trade out your nominal Treasuries for inflation bonds, own commodities, and if you have access to UCITS that trade in London there is INFU, which tracks 10-year breakevens. NASA doesn’t have a lot of good options, either, for protecting against an asteroid impact. But there are many more plausible options, if you start early, than if you wait until inflation’s trajectory is inside the orbit of the moon.

[1] Your stockbroker conveniently forgets that P/E multiples contract as inflation rises past about 3%. Also, your stockbroker conveniently abandons the argument about how businesses can raise prices before raising wages, meaning that consumer inflation leads wage inflation, when he points to weak wage growth and says “there’s no wage-push inflation.” Actually, your stockbroker sounds like a bit of an ass.